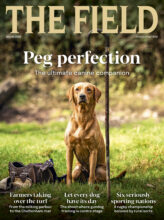

From Christmas card to winter garden, the robin signifies the festive season like no other bird, yet there is much about the species that might surprise, writes David Tomlinson

Everybody knows and loves the robin, but despite being our most familiar bird it retains a degree of mystery. Most robins hatched in Britain never move far from their birthplace, but we know that a few fly south in the autumn. One unfortunate bird, ringed in Montgomeryshire, was shot more than 1,600km away in Spain in its first winter. Why do some individuals feel the compulsion to migrate, with all the inherent risks long flights involve, when they are just as likely to survive if they stay at home?

Most British robins are sedentary. In contrast their cousins that breed in Fennoscandia and eastern Europe are highly migratory. They abandon the forests in late summer, migrating to the Mediterranean and even Morocco. Some of these birds pass through Britain but how many remain to winter here? Nobody knows. However, records show that our Northern Isles hold more robins in the winter than in the summer, so these are presumably migrants.

Though Scandinavian birds look almost exactly the same as ours, their behaviour is quite different. They are shy birds of the mixed spruce and birch forests. A friend who regularly hosts groups of Finnish bird photographers in Norfolk tells me that the Finns delight in photographing our confiding robins, as they are so much more approachable than their birds.

We are familiar with the friendly garden robin joining us when we’re digging in the vegetable patch, often coming within a foot or two of the fork, and sometimes even perching on it. It’s easy to be anthropomorphic and think that these birds not only recognise us but regard us as a friend; however, that’s not the case. They just identify the opportunity for an easy snack. In eastern Europe robins have been observed trailing wild boar rooting on the forest floor. Robins follow the fork, or the boar, because their favourite foods are insects and arthropods: the sort of creepy-crawly animals that can be found when soils are disturbed. They will happily eat anything from earthworms and spiders to caterpillars and beetles. I remember once on a chilly December day catching a large spider in my living room and throwing it out into the garden. It was pounced on almost instantly by the resident robin. I had inadvertently thrown him the robin’s equivalent of a T-bone steak. (Read more on Christmas animals by Sir Johnny Scott.)

Robins often join us in the garden but food, rather than friendship, is the motivator

Like most successful birds, robins are adaptable when it comes to food. They will readily raid the bird table, and those in my garden are keen on husk-free sunflower seeds that they take from the bird feeders. Individual robins have been seen taking crustaceans from a saltwater creek, and diving into a stream to catch tadpoles. However, the way to a robin’s heart, or at least to make it finger tame, is to provide it with mealworms. The Edwardian Foreign Secretary Lord Grey of Fallodon noted that ‘robins will risk their lives for mealworms’, adding that they were particularly easy to tame ‘in hard weather, when the birds are hungry’, but that once their confidence was established they would remain equally confiding, even when the weather is mild and food is plentiful.

Winter song

Robins are antisocial, preferring their own company for much of the year. As a result they are exceedingly territorial. The so-called ‘winter song’, usually described as being somewhat melancholy, can be heard from July onwards, uttered by the juveniles when they have finished their moult and acquired their first red breasts, with the adults starting to sing a little later when they have completed their moult. Unusually, both male and female sing to establish and maintain their territory, from which they will do their best to exclude any rivals. Suitable song posts are essential, as they are needed to advertise the territorial boundaries. David Lack, whose book The Life of the Robin, first published in 1943, remains a classic study of the species, put a great deal of effort into discovering robin territories. He found that they range in size during the breeding season from two-fifths of an acre to two acres. Pairs sometimes hold larger territories of up to three acres, but they find these impossible to defend for any length of time. Defending a territory is vitally important to a robin, and trespassers will be attacked. The ensuing battle may well lead to the death of one of the birds, though no one is quite sure how often the intruder triumphs over the territory holder. Death at the beak of a rival plays a significant role in robin mortality, and it has been estimated that it may account for more than 10% of mortality in some populations.

Robins, incidentally, are remarkably short-lived, with the average length of life a mere 13 months. However, this reflects the high mortality of juveniles, so a mature, experienced individual may well live to four or five years, with the current record held by a Czech bird, found freshly dead at the impressive age of 19 years and four months.

Robins sing from prominent perches throughout the winter

Early nesters

As robins’ lives are short, it’s essential for them to breed prolifically to maintain their numbers. They are early nesters, with birds in southern England starting nest building in March. The usual clutch is from four to six eggs, and incubation begins as soon as the last egg is laid. Hatching takes place after 14 days, and it’s another 14 days before the chicks fledge. Independence is finally gained three weeks later. During this time they are fed solely by the cock, for the female will be busy with her second clutch. By the time the eggs hatch, the cock is ready to help with feeding, as the first brood no longer depends on him.

Though instantly recognisable as robins by their shape, young birds are finely spotted until they acquire a red bib after their first moult, so by late summer most look almost identical to their parents. The plumage of both sexes is the same, and it’s only by behaviour that we can tell them apart, though of course the robins themselves don’t have any problems.

While chick survival may be poor – kills by cats are the major recovery cause for British-ringed robins – the numbers that remain are more than sufficient for the population to be maintained, and the good news is that this is one native bird that continues to flourish. The British Trust for Ornithology’s Bird Atlas 2007- 11 showed that robins breed in 94% of all 10km squares in the British Isles, and there’s no indication of any change in their status since. Thankfully, our national bird is here to stay.

Unique genus

There’s only one robin, Erithacus rubecula (technically known these days as the European robin): it’s in a unique genus all of its own and is regarded as being more closely related to the chats and flycatchers than the thrushes, with which it was once grouped. Its range extends from the Azores to south-west Siberia and includes much of Europe, though in the south of its range it is best known as a winter visitor. It breeds in almost every mainland country in Europe as well as on many Mediterranean and Atlantic islands (Malta and Cyprus being notable exceptions). In the Balearics it was first recorded breeding in 2005, and is progressively colonising the islands, while it also occurs locally in Iceland. Numbers have been increasing throughout Europe since 1980, and this is one species that it is thought could profit from climate change and milder winters.

The exquisite pink robin can be found on the island of Tasmania

Robins around the world

There are numerous birds with robin in their name to be found around the world. Perhaps the best known is the American robin, a blackbird-sized migratory thrush with brick-red breast and underparts. It acquired its name because it was the nearest bird the early settlers saw that looked anything like the familiar robin they had left behind.

In Africa there are numerous species of robin-chat, scrub robin, ground robin and forest robin, several of which sport orangered chests. The shy, secretive forest robins generally occur deep in the rainforest, where they are extremely challenging to see. One of my memorable triumphs was finally spying an orange-breasted forest robin in Upper Volta in Ghana. I noted that “it certainly acts and moves just like our robin”, but it was shy and difficult to spot in the gloom of the forest.

Australia has a wonderful selection of robins. In size, shape and appearance, if not colouring, they look like our robin but they aren’t even distantly related, their similarity being a matter of divergent evolution. My favourite is the exquisite pink robin that I have seen in Tasmania.

The most famous of all robins was Old Blue, a New Zealand black (or Chatham) robin. In 1981 Old Blue was one of just five surviving members of her species: she laid three clutches that year, saving the species from extinction. The chicks that hatched are the foundation of the current population of more than 300 individuals.

The Cape robin-chat is a common bird in South Africa but apart from an orange throat doesn’t really resemble our robin. The widespread Indian robin and oriental magpie robin are both familiar birds through much of the subcontinent but neither look much like a proper robin. In contrast, the white-bellied blue robin that I’ve watched in the hills of Tamil Nadu has the shape and appearance of our bird, though the plumage is different. However, its name has recently been changed to the white-bellied sholakili, so that’s one less robin to think about.

Symbol of Christmas

No bird, apart from perhaps the turkey, has a closer association with Christmas than the robin, and no bird appears more often on Christmas cards. The tradition of Christmas robins dates back to the middle of the 18th century, when the standard uniform of the postmen was a bright red waistcoat. Postmen thus became nicknamed ‘redbreast’ or ‘robin’, after the bird, and as a result robins, representing postmen, started appearing on the early Christmas cards. Cheap colour printing had just started, and red was an easy colour to use. (Read more on Christmas birds: from partridges to turtle doves.)

Today the connection between robins and postmen has long been forgotten, but robins remain by far the most popular birds on cards, handsomely beating partridges – usually redlegs in a pear tree – pheasants, woodcock and wildfowl. With their bright but simple colours it’s easy to appreciate the appeal of robins to the designers of cards. However, whether a bird as pugnacious as the robin is really suited to celebrating a time of peace and goodwill is debatable.