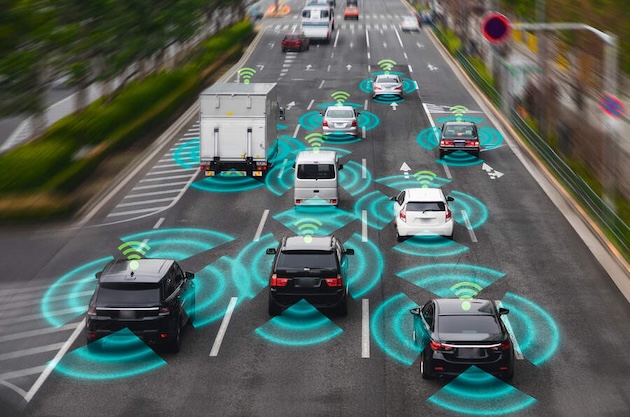

As driverless cars appear on London’s roads for the first time, Nick Herbert considers the potential benefits of – and barriers to – their widespread acceptance by the public

Would you ride in a driverless car? If the answer is ‘no’ you’re far from alone: fewer than a quarter of all road users say they would trust a driverless car or feel comfortable travelling in one. We’ll soon have the chance to decide for ourselves. Trials of ‘robotaxis’ will begin in London this spring, with two major new ventures competing to offer their rides through Uber. (Read Nick Herbert’s review of the Holland & Holland edition by Overfinch)

Waymo is already operating in six UK cities

Waymo is an American company owned by Alphabet, the parent of Google, while Wayve is a British start-up and the brainchild of University of Cambridge engineers. Waymo is already operating in six cities in the US. So perhaps I shouldn’t have been startled, while standing outside my hotel in Santa Monica last year, to see a driverless car glide by. I immediately wanted to try one out. Having downloaded Waymo’s app, I signed up with my credit card details and summoned the car. Minutes later the Waymo arrived. After I’d opened the car door on my app and got in, the car greeted me, asked me to fasten my seat belt and offered to play the music of my choice. And then we were off. Eerily, while no one sat in the driver’s seat, the steering wheel turned.

Distance and manoeuvre

I’d assumed that an autonomous vehicle would creep along but the Waymo drove purposefully, changing lanes decisively when it needed to, even when there seemed to be little available space. The powerful computers that control the car, together with its multiple cameras, radar and sensors, can judge distance and manoeuvre more accurately than we can. Or perhaps robots are just better at refusing to take no for an answer than we are.

If there’s a problem you can call an operator but I had no need. Waymo is already clocking over 250,000 fares a week and expects this number to quadruple by the end of 2026. Inevitably, there have been incidents. In October last year a Waymo killed Kit Kat, a much-loved neighbourhood feline in San Francisco, whom the car had failed to spot sitting beneath its wheels. The incident sparked local protest, with banners such as ‘Save a cat, don’t ride Waymo’.

Wayve’s ‘robotaxis’ will arrive in the capital this spring

Safety statistics

In fact, the safety statistics speak for themselves: Waymos are far less likely to cause damage or injury than human drivers. Robots don’t argue over navigation with their spouses, they don’t tire, they don’t get distracted and they don’t try to eat Big Macs at the wheel. Kit Kat’s martyrdom suggests that the real test will come if a driverless car is involved in a fatal accident. It’s not hard to imagine today’s populist MPs calling for a contemporary version of the Locomotives Act 1865, which required someone carrying a red flag to walk ahead of a self-propelled car. That reactionary legislation took more than three decades to repeal.

The car companies, however, are betting that autonomous vehicles are the future. Nissan has just signed a major deal with Wayve to use its AI technology to deliver next-generation driver assistance in its cars. Already well over a third of drivers have cars equipped with semiautonomous technology such as automatic emergency braking, lane assist and adaptive cruise control. Ford has advanced systems allowing hands-free driving, which is now legal on motorways. Your eyes still have to be on the road but that will soon change with fully automated cars where the ‘driver’ can sit like a pudding while the car does the work.

Ford’s technology already allows hands-free driving

Traffic jams, safer roads

Driverless cars have the potential to reduce traffic jams, make our roads safer and allow more productive commuting time. They could have real benefits for people who are visually impaired or disabled, and in rural areas where public transport is scarce. And the revolution won’t stop with autonomous cars. Within the next two or three years electric flying taxis will begin trials in our skies. The next generation will look back, wonder what a traffic jam was and chuckle at the thought that there was once a time when you had to drive cars yourself and cabs didn’t even fly.

This article was published in the February 2026 edition of The Field. Isn’t it time you subscribed?

Image credits from top: Alamy, Wayve Technologies, Ford