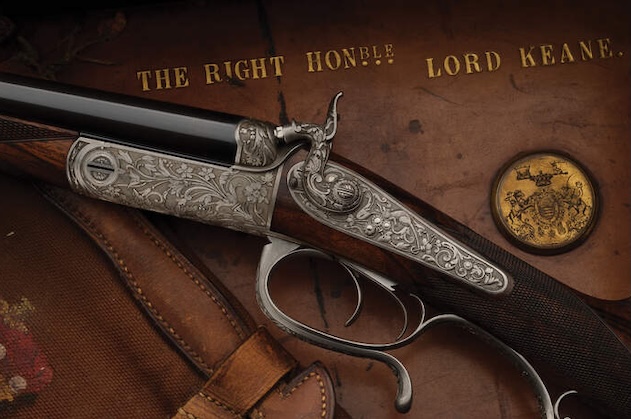

When high art meets best guns the applied arts find a perfect canvas, blending fine engraving and bespoke ornamentation to dazzling effect writes Douglas Tate

A fine pair of Purdey 12-bore sidelock ejector guns engraved by Ken Hunt

Stealth wealth is a thing of the past. Today bling is the thing and with it comes innovation, colour and texture in gunmaking. From introducing vibrant shades into the engraving process to new enamelling techniques and metalwork that resembles elephant hide, you could be forgiven for thinking Englishmen are pimping their shotguns. But ask to see the guns’ guns on any driven shoot and it becomes clear they’re not here. These high-art guns – as they are most often called – are strictly collectibles. Their particular peculiarity is that they are firearms that are rarely (if ever) fired.

When the high-art phenomena first took hold in the 1990s one gunmaker showed me a huge double rifle in a calibre designed for use in Mauser bolt-action guns. He explained to the client that he wanted to take some extra time regulating the barrels because it was the first time he had built a side-by-side intended for a round created with a single-barrelled bolt-action magazine rifle in mind. The customer, who had spent lavishly on extravagant engraving, told him not to bother as the gun would never be shot. To his credit our gunmaker regulated the barrels anyway.

The long and winding road that ends up at the door of fancy firearms can be insidious. It involves an immutable progression: fascination, accumulation, obsession and ultimately liquidation. It begins innocently with the smitten individual identifying a maker for acquisition. First any item that fits the chosen category will do; however, soon quotidian examples no longer satisfy and scarcer items are sought.

When the search for extant confections is exhausted, collectors start to commission special, individually crafted shotguns and rifles. Nothing is more desirable to collectors than sub-gauge shotguns: they are the rara avis of the bird-gun world because so few were ever made. For exactly the same reason, huge double rifles once intended for Africa’s biggest game are every bit as appealing. Unsurprisingly, when customers commission platforms for the applied arts they choose small-bore shotguns and big-bore rifles.

This Holland & Holland Royal side-by-side showcases a new pigementation process borrowed from haute horology

The history of male jewellery stretches back centuries. For the British gun trade it began in earnest with the Indian princes. I was once at an American gun show when I spotted an ornate Holland & Holland (H&H) double made for the Nizam of Hyderabad on a dealer’s table. H&H’s then managing director happened to be in the room at the time and agreed to take a look. I suggested that we were seeing the rarest of the rare. He shot me a cool look and said, “The Nizam ordered guns from us 18 at a time.”

When the Maharajas ceased to be, another H&H man, Malcolm Lyell, had the idea of a unique ornamental shotgun he called The Art of the Engraver and Embellisher. Intended as a showcase for the emerging skills of the talented Ken Hunt, it was quickly hoovered up and initiated interest in a nascent market in the US. Lyell saw an opportunity and created the ‘Product of Excellence’ series. What started as a speculative venture slowly gained traction and eventually created its own clientele.

During the 1980s, three Americans, who came to be known by their gunmakers as ‘The Three Musketeers’, entered the fray. They began ordering individually crafted pieces that had once been known as ‘presentation’ or ‘exhibition’ firearms but are now referred to as ‘functional artwork’. Friendly competition added encouragement as both purchaser and maker attempted to outdo one another. Engravers with the ability to work the hard steel surfaces of a sidelock’s multiple curves and plains were thin on the ground but the trio of Hunt, Alan Brown and Phil Coggan emerged with the evolving skills necessary to impress a demanding clientele. Listed alphabetically below are the major gunmakers that were able to secure time slots with the very best of British engravers on behalf of the ‘Musketeers’ and continue to innovate today.

(You might like to read: (the 10 most expensive guns in the world )

Holland & Holland

If any gun epitomises the sumptuous shotgun, it’s one made by H&H. No maker has created more lavish doubles than this venerable brand. The company’s efforts for the nabobs of the subcontinent established it as the ‘go to’ maker for fabulous firearms. During the Edwardian era the firm introduced enamelling (a technique that involves fusing powdered glass to a metal surface to create coloured designs) to its firearms. One example is the .375 express double rifle built in 1912 for Colonel Obaidulla Khan [which can be seen on page 102 of the writer’s British Gun Engraving]. There was a rumour that H&H guns had been enamelled to resemble Josiah Wedgwood’s ‘jasperware’ but none have yet come to light.

Starting in the 1970s H&H snagged Hunt to add silver, gold, platinum and copper to create colour scenes. But tonality was limited by the metals available. Now, H&H has introduced a colour technique that features never-before-seen subtle shading on the metalwork of one of its shotguns. “H&H’s coloured embellishment has been developed using an innovative resin compound, designed for durability and resistance to scratches. It offers extensive variance in colour application and shading, providing unprecedented artistic expression,” explains the company’s Mike Jones. These medical-grade resins coloured with organic pigments, previously only seen on high-end timepieces, are employed to create a brand-new aesthetic.

Ornamental techniques and materials have evolved but so too has subject matter. In the past a bit of scroll sufficed with perhaps a portrait of the owner’s pooch on the underside but today’s clientele are altogether more adventurous. In 2024 H&H unveiled a gun employing its new coloured resins method, featuring rainforest imagery reminiscent of Rousseau. A parrot perched on exotic foliage surveys the surrounding jungle, while a scarlet coiled snake, tree frogs, beetles and butterflies complete the scene. The bottom of the action features a leopard burning bright. Clearly H&H has retained its place in the avant-garde.

A Purdey exhibition gun engraved by French artist Aristide Barré for the 1878 Exposition Universelle.

James Purdey & Sons

Purdey’s rose and scroll engraving, celebrated for its abstemious reserve, debuted in the 1860s when James Lucas adapted designs broadly lifted from the decorative vocabulary of the Victorian era. Frank Knight’s books on the decorative arts in particular appear to have provided much of the inspiration. For more than a century, Purdey’s formula for a game gun has barely changed. Take the iconic Beesley action and cover it in conservative rose and scroll and you have the recipe for the ideal ‘best’ gun. Generations of Purdey’s gunmakers have rationalised that an elegant, well-designed gun, proportionate in every part, is what’s important and that the engraving should only be ‘simple and neat’ as emphasised in The Shot Gun (1938) by Thomas Donald Stuart Purdey and Captain James Alexander Purdey. That is Purdey’s reputation. Bling is not what Purdey is about.

But the firm also created outrageously carved champlevé (hollow background) guns and rifles for presentation to royalty and as pieces intended for international exhibitions. Beginning in the 1870s, James Purdey the Younger commissioned Aristide Barré, a French artist exiled in Britain, to decorate a small number of very special firearms. The dichotomy between Lucas’s chaste scratchings and Barre’s voluptuous carving was perfectly illustrated recently by a gun from 1893 that came to light through Holts Auctioneers and that, according to Purdey records, was ‘Chased detonating, Barry (Barre), Engraved dogs & birds, Lucas.’

Despite its reluctance, Purdey has long built guns for overseas buyers whose taste is markedly different from that of an English country gentleman. Richard Beaumont acknowledges as much in Purdey’s: The Guns and the Family (1984): ‘The Americans, in fact, both individually and through the firm of Von Lengerke & Detmold, were showing growing interest, unfortunately most of the orders specifying once again the “chased breeches and special engraving” so deplored by the Purdeys.’

Left unsaid by Beaumont is that he himself shared the Purdeys’ taste for restraint, shaped by the broad currents of their time. All felt that the finest aesthetics were expressed by the lines of a Purdey shotgun itself, yet it’s difficult to discard the notion that they were not unaware that chasing the detonators cut into delivery time and profit. ‘Engraving on a gun costs money, but because a gun is covered with heavy and elaborate engraving it does not mean the gun is of best quality,’ wrote Jim and Tom Purdey in 1938.

Like all luxury gunmakers, Purdey is influenced by market forces and if the client was sufficiently prestigious or the gig itself suggested bling, then it rose to the occasion. When artisans gathered to present their latest creations at the Exposition Universelle, held in Paris between May and November 1878, Purdey sent métiers d’art guns carved by Barré. ‘The extra Purdey exhibit consists of four guns, elaborately chased in the champ-levé style, two of which have been embellished by the talented artist Aristido Barri,’ wrote English journalist George Sala. A succession of Purdey engravers have subsequently borrowed from Barré’s style book.

“Bling is not really what we are about,” says Purdey’s Andrew Ambrose. “A significant number of the Purdeys we are building today feature the classic Purdey rose and scroll engraving design, but we do of course welcome the bespoke individual designs and ideas that clients would like to see on their guns. I would say 99% of the guns we build are shot and used and do not sit in gun display cabinets. Therefore, the clients will inevitably choose what works in terms of the gun fitting into the environment in which it will be used. We do have some heavily embellished guns coming through production with deep carved engraving, which adds a significant uplift to the total price of the gun.”

Rigby .600 nitro express rifle decorated in the totem style

John Rigby & Co

Rigby guns and rifles traditionally featured a conservative aesthetic. Dipped-edge lockplates with the maker’s name in black letter and carved leaf fences married to a simple signature scroll are both characteristic and unobtrusive. When Paul Roberts purchased the brand in 1984 he cultivated a rich client base with aspirations to revive the big double rifle, and because they are individually crafted this gave the opportunity for bespoke crafted ornamentation. What was once a useful piece of kit for stopping dangerous game became bling.

As enthusiastic collectors constructed basement showrooms intended to display their treasures, it became apparent that one defining element of the highart gun was that it would never have its bores dirtied. Since then John Rigby & Co has returned to crafting eminently practical bolt-action hunting rifles and that is now where the company’s reputation stands. But like all bespoke builders of best guns, if the client has the wherewithal and has his own ideas, Rigby will walk the extra mile.

In 2016 a client commissioned a Rigby & Co double rifle in .600 nitro express with every element of the visible steel engraved to resemble an elephant’s hide. This style of ornamentation is known as ‘totem engraving’ and it’s a radical departure from the typical representation of game animals on the playing-card-size sidelock of a shotgun or double rifle. Instead, game is represented by texture: a woodcock by its wing feathers, a crocodile by its scales and an elephant by its hide. It took until 2023 for a talented family of engravers to complete the work. It is a style that owes much to Malcolm Appleby from his time as resident engraver with John Wilkes.

One of a pair of Westley Richards sidelock ejector guns engraved with dramatic equine scenes by Paul Lantuch

Westley Richards

When the early-21st-century history of the opulently ornamented firearm comes to be written, the past 24 months will undoubtedly be described as the Westley Richards years. In that period the company has cemented its position at the heart of the high-art heap with a pair of 12-bore game guns lavishly larded with mythical horses by jeweller Paul Lantuch, a brilliant boltaction rifle engraved by up-and-comer Léo Lambert and the elegantly enamelled First Spear double rifle by Dayna White.

“Today, there is increased demand for ‘high art’,” says Anthony Alborough-Tregear, Westley Richards’ managing director, “including really interesting and unusual engraving of beasts. Some of the designs created by Paul Lantuch for us are unlike anything done before, relying on carving, multicolour gold inlays and precious stone sets. Even with traditional styles, the degree of precision and artistry applied to even well-known scroll engraving patterns is constantly being reimagined and elevated.”

Lantuch grew up in Vilnius, Lithuania and as a young artist travelled to St Petersburg to see the Hermitage collection. There he befriended the curator of arms and armour, who gave him access to areas of the collection previously denied to the public. He is the current tsar of high-art engraving. Every ‘high art’ project is discussed in length with the client to create an utterly unique piece, cost less of a concern than outright quality and individuality.

To the traditionalist heavily embellished firearms can seem a tad transgressive yet the trend shows no sign of slowing. As long as there are those willing to celebrate the individually crafted gun the health of the high-art firearm will remain robust. While the nature of ornamented shotguns may have changed over time, our fascination with them has not.

Sign up to our newsletter The Field Guide for monthly updates on guns, dogs, kit, travel and more.