Whether a dazzling spectacle or a more restrained affair, history shows us that the Coronation of the monarch is a grand ceremony steeped in centuries-old tradition, says Tony Boullemier

How many monarchs have been crowned at Westminster Abbey? Is it 38 or 39? Intriguingly, the history of the Coronation does not reveal the answer. William the Conqueror was crowned on Christmas Day in 1066 but it’s possible that Harold Godwinson, the Saxon king who got an arrow in his eye at Hastings, got there first. We know Harold was crowned on 6 January 1066 but his monks, the historians of the day, neglected to leave an official record of where. What we can be sure of is that William’s coronation was extraordinary. It was conducted in English and French, and the congregation’s roar of acclimation to appease the usurping Duke of Normandy was mistaken for a riot by troops outside. In a panic, they set fire to a number of surrounding Saxon houses in reprisal and so much smoke filled the building that the congregation fled, leaving William with the clergy to finish the service.

Not all our following rulers have been crowned at Westminster or indeed anywhere else. When Edward V, the elder Prince in the Tower, ceased to be seen at the Tower windows, his crown was put on Richard III’s controversial head instead. And King Edward VIII’s coronation was cancelled when he pledged his future to American adventuress Wallis Simpson and abdicated. Poor Lady Jane Grey, queen for just nine days, never had a crown on her fair head before it was later removed from her body. Famously, Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell wisely refused all efforts to make him a king. Indeed, while some of our leaders never had a coronation, two kings were crowned twice – and one wasn’t even a proper monarch.

Crowned not once but twice

King Henry II actually had his eldest son, also Henry, crowned at Westminster during his own lifetime. He was 15 and a real medieval celebrity: such a popular lad and awfully good at tournaments but he was a misery and complained he had no power. So, to keep him happy, his father had him crowned in 1170 as ‘The Young King’. Henry was crowned again in 1172, this time at Winchester, but was he grateful? Not a bit of it. Treacherously, he went to war against his dad but then died of dysentery after pillaging French monasteries to get money to pay his army. His father died six years later and the crown passed to his next son, Richard, the future Lionheart.

Richard I the Lionheart, King of England, painted by Merry-Joseph Blondel, 1841

Another double coronation was King John’s son Henry III, who was crowned in 1216 in a real hurry, aged just nine. It happened at Gloucester because a French army, in league with rebel barons, was controlling London. Unbelievably, the royal crown was missing, probably lost with John’s jewels in The Wash. The bishops of Worcester and Exeter performed the ceremony using a simple gold circlet belonging to Henry’s mother. When the barons came to their senses and kicked out the French, Henry was crowned again – at Westminster in 1220.

History of Coronation reveals costs

Other notable medieval coronations included Richard II’s in 1377 when the conduits of London reputedly flowed with red and white wine. While Henry VI was barely eight years old at his investiture at Westminster Abbey in 1421, having succeeded to the throne at the tender age of nine months. He also had the rare distinction of being crowned King of France in 1431. This did absolutely nothing to prevent England losing the Hundred Years’ War and pious Henry went mad twice before being murdered in the Tower during the Wars of the Roses.

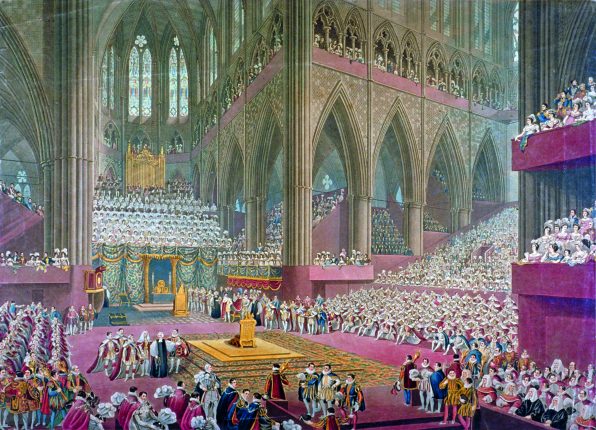

Since the late 14th century the coronation ceremony has followed the same order of service. At the time of Elizabeth I it was conducted in Latin and English, but the feisty Queen demanded so much Protestant doctrine inserting that her Catholic-leaning clergy walked out and the obliging Bishop of Carlisle to officiate. Costs of coronations have varied enormously. Thrifty Scotsman James I spent £5,000 in 1603, while parsimonious George III invested just £70,000 in 1760. However, the Prince Regent blew £238,000 to be crowned as George IV in 1821, a staggering sum for the time. He imagined he had played a big part in defeating Napoleon and when going about with the Duke of Wellington was wont to tell people, “I led a charge at Waterloo, didn’t I, Duke?” To which Wellington would reply, “I have often heard Your Highness say so.”

The excesses of George IV

The Prince wanted to mimic Napoleon’s lavish ceremony and sent his tailors to Paris to copy the Emperor’s robes at a cost of £24,000. He spent £112,000 on jewels and plate, £45,000 on robes, uniforms and costumes and £25,000 on food for his vast wedding breakfast. To pay for it all the Prince wheedled £100,000 out of the reluctant Tory government and bagged the rest out of the huge war reparations from France. Scaffolding was erected in the Abbey for 4,656 guests, all instructed to wear Tudor or Stuart costumes, and the big day was planned for 1 August 1820. But there was a snag.

George was estranged from his wife Caroline of Brunswick and she unexpectedly turned up from the Continent to claim her right to be crowned Queen Consort. Caroline was a lot more popular than her husband and when George asked the government to dissolve the marriage and remove her privileges, the bill failed to get Parliamentary support. So, the coronation was rescheduled for July 1821 and Caroline was simply written out of the service. She did not go quietly. Caroline arrived at the Abbey at 6am to be told no one could get in without a ticket. As she didn’t have one, the entrances were barred by soldiers. Caroline admitted defeat and left in her carriage to sympathetic cheers from onlookers.

Sweet Caroline

Meanwhile the King’s procession arrived at the Abbey including the King’s Herb Woman, assisted by six maids scattering petals on the red carpet. The service was followed by an immense Westminster Hall banquet. The Lord High Steward, the Marquess of Anglesey, was required to ride down the hall on his horse and uncover the first dish. Unfortunately, he had lost a leg at Waterloo. It took several pages to get him off his horse, to everybody’s huge amusement. The room was lit by 2,000 candles in 26 enormous chandeliers but they disgorged large globules of wax on to the diners below and they only escaped when the King finally rose from his table. As soon as the guests were allowed to leave their places they fell ravenously upon the leftover food. They also helped themselves to the cutlery, glasses and silver platters.

Outside were stunning fireworks, organised by Sir William Congreve, the original ‘Rocket Man’. There were illuminations, gas balloon flights and boat races and all of London’s theatres were free at the King’s expense. Alongside all this, a mob started rioting in support of the wronged Queen Caroline but the Household Cavalry dispersed it. Celebrations went on around the country with notable support for Queen Caroline. In Manchester they sang God Save the King until the free beer ran out, whereupon they switched their tune to God Save the Queen. Less than three weeks later, abandoned Queen Caroline died age of 53.

A ‘Penny Coronation’

When the largely unlamented George IV died in 1830, his successor William IV had to be persuaded to have a coronation at all. Clearly, he felt obliged to economise and his own ceremony was known as ‘the penny coronation’ and cost around one-sixth of what George IV had spent. The egregious banquet was scrapped, huge ceremonies and processions involving peers were dropped and there was more of a focus on the state procession to the Abbey in coaches, which survives to this day.

A portrait of Elizabeth II wearing the crown of the kings and queens of England for her coronation in June of 1953

Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation in 1953 was a glittering jewel in the drab post-war years. It cost an estimated £1.57 million – equivalent to more than £43 million today. It was the first to be televised and many families bought TV sets or rented them for the day. There were 8,000 guests and the procession was two miles long, including 29,000 service personnel and heads of Commonwealth countries. So many carriages were needed that some were borrowed from Elstree film studios. The Queen’s dress was embroidered with the floral emblems of Commonwealth countries and she wore the Coronation Necklace that had been commissioned by Queen Victoria and worn by Queens Alexandra and Mary, and The Queen Mother at their coronations. Her 51/2-metre-long silk velvet cloak was carried by seven ladies-in-waiting. However, the friction between her robes and the Abbey carpet made it so difficult to move that she had to beg the Archbishop of Canterbury to “Get me started.”

The Queen was anointed with holy oil, a secret recipe based on sesame and olive oil with many fragrances. It was applied with the 12th-century Coronation Spoon but Elizabeth requested that this part of the ceremony should not be televised. She received the Sword of State and was invested with the Armills (bracelets), Stole Royal, Robe Royal and the Sovereign’s Orb, followed by the Sovereign’s Ring, the Sovereign’s Sceptre with Cross and the Sovereign’s Sceptre with Dove. It seemed to those watching an awful lot to carry. The Sceptre with Cross and the Orb date back to 1661, as does St Edward’s Crown, which weighs nearly 5lb. This was made for Charles II’s coronation.

What to expect at this Coronation

What a relief it would have been for the late Queen to leave the Abbey after the three-hour ceremony wearing the somewhat lighter Imperial State Crown, weighing just 2.3lb. This was made in 1937 for King George VI and replaced the crown made for Queen Victoria in 1838. HM King Charles III will also wear both of these crowns on 6 May, when The Queen Consort will be crowned alongside him. His pared-down Coronation is expected to last just over an hour with 2,000 guests and will be a simpler, shorter and more diverse service. It will “look towards the future, while being rooted in long-standing traditions and pageantry”. And it is hoped that the services of the London Fire Brigade will not be required.

Tony Boullemier is author of The Little Book of Monarchs. The Field is packed with Coronation content. Click here for a guide to the procession. Are you having a street party to celebrate the Coronation? Read our guide to planning a celebration fit for a King here. We’ve also compiled a handy guide to the must-buy Coronation products.