When Charles Dickens published A Christmas Carol over 175 years ago, he created a blueprint for the season that continues to haunt us to this day, says Sarah Pratley

Shocked by the effect of the Industrial Revolution on working children, Charles Dickens planned to write a political pamphlet. Instead he published A Christmas Carol, with a festive blueprint that continues to haunt us to this day, says Sarah Pratley.

From Christmas cards with proper country credentials to introducing game to the festive spread, The Field is the ultimate guide to a proper, British Christmas. Read The Field’s British Christmas.

The Field is the original, and ultimate, sporting journal, covering everything rural types care about since 1853. SUBSCRIBE today and get your first six issues for JUST £6 by clicking on THIS link.

A CHRISTMAS CAROL

A family, a feast and a fire warm the hearth at Christmas. This is a scene oft reproduced on Christmas cards, the setting for numerous festive stories and an idyll many attempt to emulate. It is also distinctly Dickensian.

Such levels of festive perfection are expertly conjured up by Charles Dickens in A Christmas Carol, published in 1843 – over 175 years ago. From the “cold, bleak, biting weather” of the novella’s opening to the merriment of old Fezziwig’s ball and the Cratchits’ Christmas feast, the scenes written close to two centuries ago are so familiar they feel timeless. For Dickens’ contemporary reader, however, the novella did not reflect the Victorian norm.

John Leech’s book illustration of the Ghost of Christmas Present.

Christmas was a public festival during the Middle Ages, with villagers gathering in the squire’s great hall for feasting and games. By the 1800s, interest had faded. The Industrial Revolution had scattered rural communities as they followed new jobs to inner-city homes. Long, unregulated working hours and little or no holiday made the Twelve Days of Christmas a laughable impracticality. Indeed, Scrooge is reluctant to give his clerk, Bob Cratchit, just one day of holiday, something he considers “not convenient” and “not fair”. In 1807, poet Robert Southey remarked “in large towns the population is continually shifting; a new settler neither continues the customs of his own province in a place where they would be strange, nor adopts those which he finds, because they are strange to him”. In 1808, Sir Walter Scott practically wrote the festival off as forgotten: “England was merry England, when/Old Christmas brought his sports again.” By the 1820s, writer Leigh Hunt disregarded Christmas as “scarcely worth mention”.

But the tide was turning. “From the 1820s onwards, there was more interest in reviving a traditional Christmas,” says John Bowen, President of the Dickens Fellowship and Professor at the University of York. “Prince Albert was about to bring the Christmas tree to England, the first Christmas cards were sent in the 1840s and carols were brought back in the ’20s and ’30s.” Indeed, 1822 saw the publication of a collection of Ancient Christmas Carols. Prince Albert first installed Christmas trees in the palaces in 1840. New Year’s Day was traditionally the day for gift-giving but Albert had changed this to Christmas Day by 1841. In 1843, the year A Christmas Carol was published, the first Christmas card was commissioned. By 1880, 11.5 million cards were produced.

CHRISTMAS FOR THE WORKING CLASS

Prior to this revival, Christmas was not the defunct festival Scott and co would have us believe. “Christmas was celebrated but wasn’t as popular,” says Louisa Price, curator at the Charles Dickens Museum, formerly the author’s home at 48 Doughty Street, London. “It was celebrated more in rural areas and working-class communities.” One of these communities was Dickens’ own as a boy. “His grandparents were servants at Crewe Hall and there were always very large parties there. His headmaster was known for Twelfth Night parties. As a young boy, Dickens was in an environment where Christmas was loved and celebrated,” Price explains. It was an environment the author continually sought to recreate. Like the parties at Crewe Hall, Fezziwig’s ball in A Christmas Carol involves “dances, then there were forfeits… and there were mince pies, and plenty of beer”, and includes everyone from “the three Miss Fezziwigs” to “the housemaid”. Dickens himself was known for hosting. As one of his sons recounted, at Christmas, “my father was always at his best, a splendid host, bright and jolly as a boy”.

“Dickens loved to host at Doughty Street and beyond, and not just at Christmas,” says Price. “His wife wrote a cookbook, a little-known fact as she wrote under another name. It included menu plans for many guests.”

48 Doughty Street, formerly the author’s home and now the Dickens Museum.

The year 1843, however, was not filled with jollity for Dickens. “Martin Chuzzlewit was not doing very well, American Notes had come out and been very badly received in America and his family was growing,” explains Price. All was not well in the wider world, either. “England was in a bad state,” says Bowen. “The 1830s were known as the Angry Thirties and the 1840s as the Hungry Forties. Working people suffered terribly.” In February 1843, The Second Report of the Children’s Employment Commission was released, detailing the horrifying effects the Industrial Revolution was having on working children. “Dickens was shocked by these political reports,” says Bowen. “Dickens felt it so personally because at 12 he had to look after himself. He was working 12 hours a day in a rat-infested warehouse and he was walking 40 miles a week.” In a letter to Thomas Southwood Smith, Dickens admits to feeling “so perfectly stricken” by the report that he was considering releasing a pamphlet entitled An Appeal to the People of England, on Behalf of the Poor Man’s Child. The pamphlet never appeared but it’s no coincidence that A Christmas Carol did. “He understood that if he was to write a political pamphlet the readership would be limited, and that with a short novella published at Christmastime, for an emerging market for books at Christmas, the effects would be far greater,” says Price.

Dickens was right. Released on 19 December 1843, the first print run of 6,000 copies sold out by Christmas Eve. Second and third editions were released before New Year and the novella has never since gone out of print. Carol became Dickens’ biggest success across the Pond, too. Within a few years, sales had outstripped even those of the Bible. “It has had an amazing afterlife,” asserts Bowen. The story was adapted for stage immediately. Three productions opened in London on 5 February 1844 and by the end of the month a further rival five were playing. “Carol, as Dickens knew himself, really lends itself to adaptation and performance,” says Price. The novella was a favourite at Dickens’ public readings and formed the first half of his final performance. But the story lives on with many revisiting it every Christmas. “We always have several performances of Carol at the museum,” says Price. “We have people come year after year, for many it’s a tradition to hear Carol at Christmas”. Today, the adaptations are endless. “There’s even been a Carol ballet, an opera, a mime,” enthuses Price. From stage to screen to The Muppets – even Scrooge would be hard-pressed to avoid Carol at Christmas.

A CAMOUFLAGED POLITICAL PAMPHLET

Critics received the novella as enthusiastically as the public. In January 1844, the Sunday Times stated, “the whole economy of the work is perfectly delightful, and its moral purpose deserving of the highest praise”. The novella is, after all, a camouflaged political pamphlet. Dickens makes this clear at the outset: “I have endeavoured in this ghostly little book, to raise the Ghost of an Idea… May it haunt their houses pleasantly, and no one wish to lay it.”

“The précis to Carol I particularly like,” shares Price. “Dickens wanted to lay this idea within people’s minds and within homes at Christmastime – a time we think about family – to make readers see it as a time for charity and goodwill.”

“Dickens was a sincere Christian but undogmatic,” says Bowen. “The people he admired were people who made Christian values work in the world. Carol is not about Scrooge going to heaven, it’s about being ‘as good a man, as the good old city knew’.” Indeed, Scrooge at the story’s close has nothing of the opening’s “squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous old sinner”.

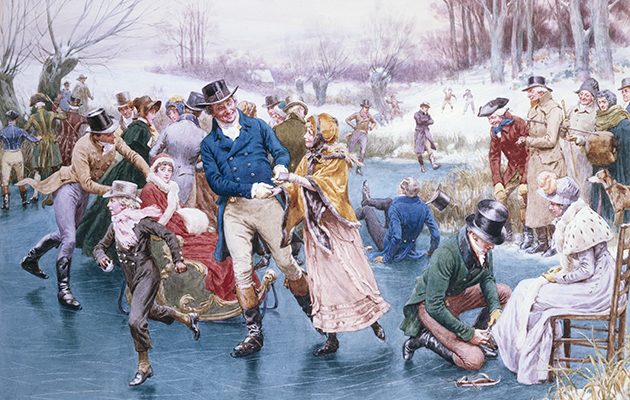

John Leech’s Mr Fezziwig’s Ball.

“Scrooge goes on a great, long journey,” explains Bowen. “First with the Ghost of Christmas Past he feels sorry for himself, and by feeling sorry for himself he can then learn to feel sorry for other people.” Scrooge isn’t alone on this journey – Dickens takes the reader along for the ride. “There is a real sense of danger and dread if change doesn’t happen,” says Bowen. “Dickens can be quite tough.” The fate of Tiny Tim is not decided by the severity of his illness but by the actions of society. “If these shadows remain unaltered by the Future, the child will die,” Scrooge is warned. It is a warning that reformed Dickens’ readers as immediately as it did Scrooge. William Makepeace Thackeray declared that A Christmas Carol “occasioned immense hospitality throughout England; was the means of lighting up hundreds of kind fires at Christmas time; caused a wonderful outpouring of Christmas good feeling”. The Gentleman’s Magazine attributed the rise of charitable giving in early 1844 to A Christmas Carol. Within just a few years of its publication, workhouses were serving Christmas dinners and many businesses closed for the holiday. In 1867, an American businessman was so moved by the story he closed his factory on Christmas Day and sent every employee a turkey. “It makes people imagine Christmas as a festive, celebratory time, when you reach out from your own family to other people outside your own little world,” asserts Bowen.

Dickens became so synonymous with Christmas that when he died in 1870, a barrow-girl in Drury Lane was heard asking, “Mr Dickens dead? Then will Father Christmas die too?” It is testament to the power of Dickens’ writing that his notion of Christmas as a season of goodwill did not die with him. The ghost created in A Christmas Carol continues to “haunt their houses pleasantly”, encouraging us to open our hearts and give generously. At over 175 years old, there is plenty of life in it yet.