By turns impressive and delightfully eccentric, follies became a way for the aristocracy to express their individuality away from the practical constraints of the big house says Simon Scott

What is a folly? At times it seems as though there are as many definitions as there are follies themselves. The Oxford English Dictionary describes it as: ‘A costly ornamental building (considered as) serving no practical purpose.’ Intriguingly, the word derives from the French folie meaning ‘madness’ yet can also mean ‘delight’. Both words are key constituents to our understanding of a folly.

THE FOLLY OF FOLLIES

Belvedere, eye-catcher, gazebo, grotto, obelisk, pavilion, pyramid, rotunda, ruin, sham building, temple, tower – all can be considered as follies, yet not all are. Architectural styles typically range from battlemented Gothic to the classically inspired Greek and Roman. A true folly probably defies definition as the accolade is in the eye of the beholder, the visitor. Maybe architectural historian Gwyn Headley is correct when he states: “Follies are misunderstood buildings.” A good legend also helps.

Golden age

The golden age for folly building started in the 18th century and was largely driven by the aristocracy’s penchant for the Grand Tour, bringing back both physical souvenirs such as statuary and paintings as well as ideas. They saw the ruins of the ancient Greek and Roman empires, discovered for themselves the architectural theories of Palladio, Serlio and Vitruvius, and expanded their social circles while also opening their minds to all that surrounded them.

Back in England, magnificent stately homes were constructed in the fashionable European styles, designed by the likes of James Gibbs, Robert and James Adam, William Kent, Sir William Chambers, Sir John Vanbrugh and Sir John Soane. However, the designs for many of these structures were, by practical necessity, largely formulaic. Inside almost every one you will find a grand entrance hall on the piano nobile with dining room, saloon, long gallery, library, ballroom and music room as well as multiple antechambers and bedrooms, staff quarters in the attic, with kitchens below stairs. Where to express individuality?

In the garden or wider landscape there were no such needs for practicality. In the great outdoors, aesthetics were the prime consideration. Here the owner and architect could design a structure free from constraints: a folly. Sometimes these structures would make political statements, such as those found in the landscape at Stowe in Buckinghamshire; sometimes simple ostentatious displays of wealth, of which the Archer Pavilion at Wrest Park in Bedfordshire is an example; sometimes sexual, as with the Temple of Venus at West Wycombe in Buckinghamshire; and sometimes to show the family’s ancient lineage, for instance Stainborough Castle in Yorkshire.

Prominent designers

Many of the grandest follies at the grandest country piles were created by the same professional architects responsible for the main houses. The designers of the surviving follies at Stowe read like a veritable Who’s Who: Sir John Vanbrugh designed the Rotunda and Lake Pavilions; James Gibbs the Boycott Pavilions, Bourbon Tower, Temple of Friendship, Queen’s Temple, Gothic Temple, Fane of Pastoral Poetry and Stowe Castle; while William Kent was behind Oxford Lodge, the Temple of Ancient Virtue and the Temple of Venus. Meanwhile, Robert Adam designed the south façade of Stowe House itself. An amazing collection of follies in one landscape, for there are more follies at Stowe per square yard than anywhere else in the world. Even more impressive when one realises that many have been lost over time.

Stowe was the seat of the aptly named Sir Richard Temple, a prominent Whig, and the gardens make many political statements. One example is the beautifully proportioned Temple of Ancient Virtue designed by Kent, an Ionic version of the Temple of Vesta at Tivoli. This rotunda is Roman in design, yet Rome was considered a dictatorship, while Greece was the home of democracy and liberty. Consequently, the domed interior was originally embellished with statues representing the Greek heroes Homer, Socrates, Epaminondas and Lycurgus, respectively thought the greatest poet, philosopher, general and lawgiver of the ancient world. In complete contrast, just south of the Temple of Ancient Virtue originally stood the Temple of Modern Virtue. This was a satirical comment on the politics of the day with the headless statue of Prime Minister Sir Robert Walpole standing among an uncouth, ruinous structure. Contrasting ancient and modern virtue meant that, to all intents and purposes, the 18th-century landscape at Stowe was a 3D equivalent of today’s Private Eye.

Yet most follies were not political. Nor were they the work of professionals but of landowners themselves. Some were recognised as designers in their own right, such as William Wentworth, Earl Strafford (1722-91). Lord Verulam wrote that ‘Lord Strafford himself is his own architect and contriver in everything’, while Lord Wharncliffe described him as ‘eminently skilled in architecture’. The wonderfully eclectic group of follies at Boughton Park near Northampton bears witness to his talent, with predominantly Gothic structures across a designed landscape. Wentworth was not alone in his endeavours. Aided by architectural pattern books from the likes of Gibbs, the Adam brothers and the rogue Batty Langley, many of the landed gentry were fully capable of creating their own follies to enhance their Arcadian landscapes. Others such as Alexander Pope, Lord Burlington and Horace Walpole were what we would call today key ‘influencers’.

Horace Walpole (1717-97) of Strawberry Hill fame, and a close friend of Wentworth, astutely commented that ‘in general it is probably true that the possessor, if he has any taste, must be the best designer of his own improvements. He sees his situation in all seasons of the year, at all times of the day. He knows where beauty will not clash with convenience, and observes in his silent walks or accidental rides a thousand hints that must escape a person who in a few days sketches out a pretty picture, but has not had leisure to examine the details and relations of every part.’

Consequently, most follies were as individual as their owners, and some of those were very eccentric indeed. Witness ‘Mad Jack’ Fuller (1757-1834). At first glance he was notable for being educated at Eton, having lost his father aged just four, before inheriting the Rose Hill estate (now Brightling Park) in Sussex. Aged 23 he was elected as a Member of Parliament, serving from 1780-84 and 1801-12. He was a renowned philanthropist and patron of the arts and sciences, buying Bodian Castle to save it from destruction, commissioning many paintings from JMW Turner and acting as sponsor and mentor to the young Michael Faraday.

What makes Mad Jack interesting to the world of follies are his architectural indulgences, possibly aided by his fondness for drink. Indeed, in 1810 he had to be removed from the House of Commons. Hansard states he was ‘very violent and disorderly’. Although he built a number of follies on his estate, including a relatively routine rotunda apparently famed as the location for bawdy parties, the Pyramid and the Sugar Loaf are his follies worthy of special attention.

The 25-foot-tall Pyramid is actually Mad Jack’s mausoleum and was built in the village churchyard. As with all good follies, one never knows when reality stops and legend starts. According to folklore, Mad Jack did not just want to have a pyramid for his mausoleum; he reputedly also gave specific instructions for his internment. He was to be seated, fully dressed, on an iron chair in the centre of the Pyramid with a bottle of port and a roast chicken for sustenance while he awaited resurrection. And, just in case the devil arrived first, the floor was to be strewn with broken glass to cut his hooves. Sadly, when the Pyramid was restored in 1982, it was found that Mad Jack was buried quite normally under the floor.

The second Mad Jack legend relates to an unusual 35-foot cone-shaped structure resembling an old-style sugar loaf. Lore has it that one evening Mad Jack was dining with friends and, in a drunken state, boasted that he could see the spire of Dallington church from his dining-room window. It was dark but several of his friends knew that the church was in a valley and not visible. Bets were made with Mad Jack confident of success. Imagine his horror when he soberly opened his curtains the following morning and realised his friends were right. What he did next was what all good folly builders would do: hastily erect a spire to win the bet. Amazingly, this legend has a ring of truth about it. When restoring the Sugar Loaf in 1961, builders found it was made of nothing more than stones and mud, suggesting it had indeed been put up in haste.

Today, there are still folly builders. Companies such as Somerset-based Redwood Stone provide impressively antique-looking stonework to build your own Gothic folly or ruin. There are multiple standard kits to choose from or you can go for something designed to order. Elsewhere, at the Forbidden Corner near Leyburn in North Yorkshire, folly building has become a tourist attraction with an enthusiastic client and architect working together to cleverly utilise all sorts of reclaimed and new materials to create a mesmerising collection of buildings. Others build privately for enjoyment out of the public eye, whether in a suburban back garden or on a large country estate. In many ways, not much has changed over the past 250 years. Enthusiastic amateurs, landed gentry and design professionals are still inspired to act together or in splendid isolation to create quirky garden buildings called follies. Long may it continue.

Simon Scott is a folly designer and author of The Follies of Boughton Park. To find out more about follies in the UK, track down a copy of Follies by Gwyn Headley and Wim Meulenkamp, subscribe to thefollyflaneuse.com and join the Folly Fellowship (follies.org.uk), founded in 1988 to protect, preserve and promote follies, grottoes and garden buildings.

FABULOUS FOLLIES

THE SPECTACLE, BOUGHTON PARK, NORTHAMPTON

An eye-catcher folly nonpareil. Built in around 1770 by William Wentworth, Earl Strafford, to mark the edge of Boughton Park and frame Moulton Church in the distance.

THE PINEAPPLE, DUNMORE, STIRLINGSHIRE

An eccentric structure built of the finest masonry. This unique folly was created between 1761 and 1777 for the Earl of Dunmore and presides over an immense walled garden.

JACK THE TREACLE EATER, BARWICK HOUSE, SOMERSET

The quirkiest of all follies. A rough rubble arch about five metres high, supporting a circular tower with a conical roof surmounted by a lead statuette of Mercury.

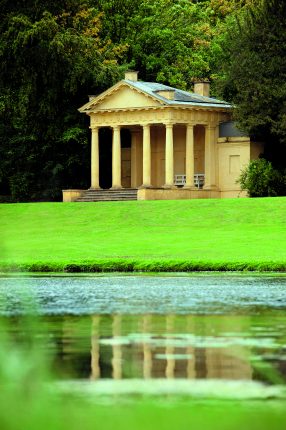

TEMPLE OF ANCIENT VIRTUE, STOWE, BUCKINGHAMSHIRE

Stowe is the ultimate folly landscape in the UK. This politically charged temple was designed by William Kent.

RUINED CASTLE, HAGLEY HALL, WORCESTERSHIRE

Considered the most perfect of sham ruins, famously described by Horace Walpole as having ‘the true rust of the Barons’ Wars’. Built between 1747 and 1748 to Sanderson Miller’s design. Miller was the pre-eminent creator of such follies in that period.