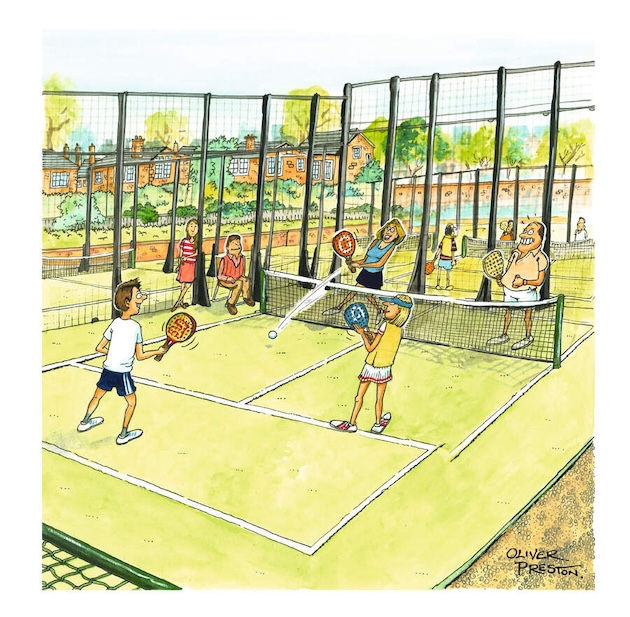

Padel is picking up steam in Britain but what makes this new racket sport so universally appealing?

Padel involves a decompressed ball being hit over a low net on a rectangular court measuring 10 metres by 20 metres. It uses the same scoring as tennis and, while there are some singles courts, it’s mainly played as doubles. And although the Brits were a little sluggish to adopt it, we’ve now tapped into the fun this set-up ensures, which has already been spotted by our European neighbours. The International Padel Federation was established in Madrid in 1991, and padel seems on course to become an Olympic sport in 2032. In Spain it has 3.7 million players and is bigger than tennis, and it’s second only to el fútbol in soccer-mad Argentina. There are 900 courts in Italy and 1.5 million players. Over half a million Frenchmen play each year, and even more in the Netherlands.

And although the Brits weren’t the first out of the blocks, we’ve now made up for lost time. The first court was constructed at the Harbour Club in Chelsea but it wasn’t until 2011 that the David Lloyd enterprise introduced the game to its franchise. Five years ago there were only 40 courts nationwide but we now boast around 90,000 players and 500 courts – and these numbers are increasing all the time. (Read: anyone for real tennis?)

But what is it that is driving this surge? While it’s not always easy to articulate what one enjoys about any activity, discussing padel with enthusiasts – they rarely seem to be just players – certain key aspects emerge. Participants revel in how easy it is to play, at least at a basic level. Played as doubles on a court roughly a third of the size of a tennis court, it lends itself to rallies as players have less area to cover. “It’s the most accessible sport I’ve ever encountered,” declares Gareth Quarry, an early adopter of the game a quarter of a century ago and one who has since built four courts in his houses in Richmond, Spain and Portugal. His wife and four children all play, and he runs a family investment fund that invests in padel among other ventures: “Even if you’ve never played before, you can get on a court and have a decent rally.”

Simple and sociable

This sentiment is echoed throughout the padel community. Like Quarry, Timothy Edwards took up padel in the late 1990s at the Harbour Club. “It’s easy to pick up when you first start playing. If you have two players of a similar standard playing alongside two total beginners, you know you’ll have a pretty good game,” he insists.

Charlie Grave is the co-founder and tournament director of the Padel Classic. He observes that “racket sports such as tennis and squash are technically quite difficult but padel puts its arms around everyone”, and notes that for this reason it’s proving popular with cricketers and footballers too, and even the rapper Stormzy. It’s therefore a great introduction to racket sports for children. My daughter Ottilie, 11, has been playing now for three years, having taken it up after tennis proved beyond her skill set. “Even if you’re uncoordinated, you can enjoy it. It makes you want to play better,” she says. Indeed, padel has been great for her confidence. Karen Hazard coaches Ottilie at The Hurlingham Club, and explains why it’s such a great game for the young: “Padel promotes fun, fitness and skill development for children. It’s also such a simple and sociable game to play, so it’s something families can do together.”

Tom Bolton recently spent the half-term holiday in the middle of his A levels playing padel in Andalusia rather than revising. “The magic of padel is that it transcends specific demographics and is truly open for everyone to try. You can get your backside kicked by a nearing-immobile old person or an eight-year-old who is technically skilled and doesn’t stop running,” he says.

Bolton has spotted a key demographic here: padel is just as popular with older players, as the smaller court requires less mobility. “For many ageing athletes padel is much easier on the body,” believes Frederika Adam, photographer and racket sport legend, who was introduced to the game by Quarry 14 years ago. A keen real tennis player constrained by the fact that there are only 48 courts worldwide, she also appreciates the availability of padel courts pretty much wherever she travels in Europe and the USA.

Touch and subtlety

While, as Quarry notes, there’s “a low barrier to entry”, to play padel well requires serious skill. John Schmitt, a barrister in his early forties (and uncle to Ottilie), plays every Monday evening at The Hurlingham Club as part of a regular foursome with whom he’s been playing tennis for 30 years. He enjoys the longer rallies encouraged by the small size of the court and the number of players but observes that it’s “strategic and requires precise placement” to play well.

This more sophisticated complexity and accuracy endears padel to players of other racket sports. George Spalton KC is part of Schmitt’s Monday foursome, and summarises it thus: “Padel combines the guile and age-old techniques of real tennis, the spirit of lawn tennis, the speed of squash and the fun of table tennis.”

Adam explains further why it’s so popular with real tennis players who are, of course, well versed in dealing with the walls: “The serve is a placement shot and power is unnecessary if you can’t control it. The points should last 10, 20, even 30 shots, and once you start to control the pace and placement of these shots, like real tennis, it’s a clever game of cat and mouse.” The fact that power is unnecessary means women can play against and alongside men on a level playing field. “Padel isn’t about brute force,” says Quarry. “There’s a lot of focus on touch and subtlety.”

There are rewards to learning this level of control, not least that it encourages longer rallies. “The whole point of padel is the long rallies. Because it’s played by four people in a tight space, hitting a winner can be hard. Long rallies are indicative of a higher standard of play,” explains Hugo, Quarry’s son. “As you get more comfortable on the court, particularly using the walls, there starts to be a rhythm to the points, almost like a dance. As the rally continues, players can find themselves doing what they never thought they were capable of.”

But lest this focus on perfecting one’s game is off-putting, the final and perhaps most important reason why padel is in the ascendent is that it’s so enjoyable. Quarry has “never played without having a laugh” and similarly Edwards has “never come off without having had fun”. Four people playing a fast-paced game in close proximity lends itself to “banter and quips” in a way that lawn tennis doesn’t, according to Edwards, and newcomer Bolton already appreciates “the camaraderie in the game” compared with the more solitary aspect of its forebear.

Indeed, it’s the fun offered by padel, coupled with its accessibility, that has given Quarry a vision: a padel court for every school in the country. “We need to get society moving again. I’m passionate about sport for kids, and deplore the fact that virtually every state school has lost its playing fields. Because the court is small, padel has a small footprint and children can play straight away. I want to persuade the Government to introduce padel at every school.” This is, of course, a radical idea but not an impossible dream. If Quarry succeeds, the future of racket sports in this country will look very different indeed.

Padel power

And change is already afoot. Padel was brought under the auspices of the Lawn Tennis Association (LTA) in 2020. While this decision wasn’t without its critics, Edwards, who was vice-chairman at the time, describes it as a masterstroke because as an official sport it is recognised by Sports England and becomes more attractive to investors and more acceptable to planning authorities. While there is apparently a bottleneck of planning applications, the LTA announced a strategy last year designed to increase numbers and accessibility.

The first phase of the strategy aims to increase numbers from 129,000 to 400,000, and monthly players from 65,000 to 200,000, and to double the number of courts to 1,000 by the end of 2026. Charlie Grave thinks that for padel to be really accessible, twice that figure will in fact be necessary. It will also mean boosting the number of coaches, and the LTA is hoping to increase the ‘padel coach and activator workforce’ from 40 to 700. It envisages that this will see 10 Brits in the top 200, and two in the top 100 worldwide.

This won’t be cheap, of course – a standard court costs around £65,000 and a fancy one around £75,000 (four standard tennis courts cost up to £200,000). And even this doesn’t include a roof to protect the traditionally open-air padel courts from the vagaries of the British weather. Hugo Quarry installs retractable roofs at a cost of more than £45,000 that, while a significant outlay, would radically increase the conditions in which padel can be played. Indeed, the future for padel could be very sunny indeed.