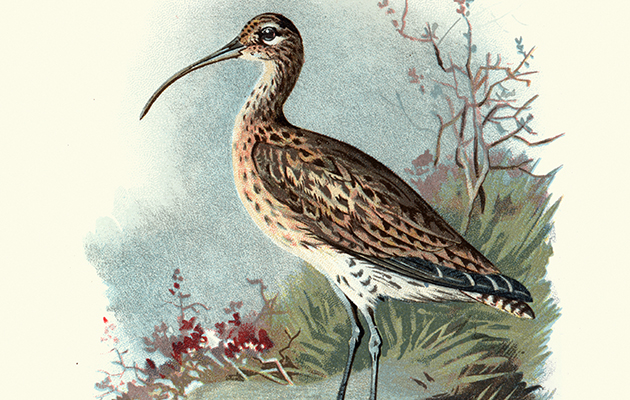

This delightful wader, now a red-listed species, is disappearing from our shores. What must be done to halt this decline, asks Ian Coghill

Though the curlew is much-loved by the masses, there are now just 66,000 breeding pairs in the UK and it is on the Red List of Conservation Concern. What must be done to halt the decline of this delightful wader, asks Ian Coghill.

For more on how vital our grouse moors are, read new study reveals the great benefits of grouse shooting to moorland communities.

THE CURLEW: RED-LISTED

The shooting community labours under a profound misapprehension. It is widely, and not unreasonably, believed that if we can demonstrate that estates managed for shooting are rich in biodiversity, provide safe havens for rare birds and other wildlife and they protect beautiful landscapes, the RSPB will be delighted and tell the world that we are good boys and girls who should be treated as the dedicated conservationists we undoubtedly are. But nothing could be further from the truth. Based on long, personal experience, I believe that it would be difficult to find anything that annoys the RSPB strategists more than the news that a properly managed shooting estate is an exemplar of good conservation practice.

There are now just 66,000 breeding pairs in the UK.

The reason for this is simple: they rely for their funding on the public believing that without them the UK’s wildlife is going to hell in a hand cart. That they, and they alone, know how to fix things, and if they are only given enough money all will be well. There is nothing they cannot fix. If that is the way you raise the £140 million you need to run your organisation, in the manner to which it has become accustomed, the last thing you need is some ghastly shooters achieving far better results, funded out of their own pockets.

If you don’t believe me, consider the curlew. To say that it is loved is a profound understatement. I have never met anyone who is not a fan of this remarkable bird. Those who spend their time on our estuaries and grouse moors could be excused for thinking that these wonderful, enigmatic birds are doing well, perhaps as well as ever. They would be profoundly and tragically wrong. Over much of its traditional British range the curlew is in dire straits, if not already locally extinct. Places where people took for granted that the spring would be enriched by the sounds of curlew returning to their ancestral breeding meadows and moors, are now silent. Generations are arising who are not even aware of what has already been lost. The species is slipping into history.

The UK has nearly 30% of the world’s breeding population of curlew.

The world’s curlew species are not in good shape; the eskimo curlew and the slender-billed haven’t been seen for years and are almost certainly already extinct. Our own bird, the European curlew (Numenius arquata), is disappearing from huge swathes of these islands: virtually extinct in the Republic of Ireland and Ulster; hanging by a thread in Wales; only a couple of hundred pairs in England south of the Peak District; population down 60% in Scotland. To make things worse, unlike some species that could do better in this country, they are not underwritten by huge, successful populations elsewhere. We have nearly 30% of the world’s breeding population and it is doing no better abroad than it is here.

They face a loss of suitable habitat and in areas of improved grassland their eggs and chicks may be destroyed by silaging, but neither of these are their biggest problem. There is no silage cut on prime habitats like Dartmoor, the Irish peat bogs, the New Forest heaths or the Welsh moors. Predation is far and away the largest threat. Over a decade ago the GWCT demonstrated in the Otterburn trial, one of the most robust and elegant experiments of its kind, that in perfect habitat, but without gamekeepers, curlew breeding success was insufficient to maintain their population. Conversely, with effective gamekeeping, curlews produced a healthy surplus of fledged chicks and, over time, the number of breeding pairs rose steadily.

CURLEW COUNTRY

The malign influence of predation on the curlew population was demonstrated with less scientific rigour, but perhaps greater force, by a project in Shropshire, Curlew Country. This monitored the fate of eggs and chicks in what is the last redoubt for curlew in a county where they were once widespread. The Onny and Camlad catchments west of the Long Mynd held 20 to 30 pairs and every effort was made to find nests and monitor their success. In the event, there wasn’t any success to monitor. In the first two years of the study, virtually all the nests were destroyed (mainly by foxes, badgers and corvids). The few chicks that hatched in the second year, thanks to electric fences thrown round them to keep foxes and badgers at bay, were all predated before they could fledge. Predator control in subsequent years resulted in an improvement but it meant that getting funds from the usual sources became next to impossible. Such money as was forthcoming often specifically excluded dealing with the very issue that was driving the birds to extinction.

Eggs and chicks are predated by foxes, badgers and corvids.

Obviously, as the largest and richest bird protection charity in the world, the RSPB is aware of the peril faced by the curlew. It is fully aware of the Otterburn research and what happened in Shropshire. The charity knows that whilst modern farming has been a major problem in some areas, it is not a problem over huge swathes of the uplands, which historically held large numbers of curlew and now hold none. Faced, for more than a decade, with the unpleasant reality of the scientific evidence, it reacted by running its own experiments, comparing predator control with habitat manipulation. These were not, as was admitted to me and others, in any sense akin to the elegant and incontrovertible science of Otterburn. They were suck-and-see attempts at blundering onto a way of avoiding what every unbiased person already knew: that, without efficient legal predator control, curlew have little chance of long-term survival as a breeding bird.

The RSPB can hardly say it didn’t know. Even if you ignore the science, it has been managing high-grade curlew habitat for years. When the charity took control of 8,000 acres of moorland and pasture at Lake Vyrnwy, it said that, “Because of the regime of burning and despite grazing the moorland, there is still a fairly healthy population of red grouse and large numbers of breeding curlew.” That was in 1984. Last spring, one pair tried to breed but the nest was predated. Large numbers down to one failure is, by any unbiased judgement, failure.

Curlew numbers have plummeted a the RSPB’s Lake Vyrnwy reserve.

Where have they been successful in reversing the decline? Where can they point to outstanding success? They may have slowed declines, but that is largely the result of curlew being long-lived birds, so extinction is delayed. Equally, and more worryingly, they may have created curlew sinks. Places where pairs prospecting for a nest site are drawn in by the excellent habitat, only to have their eggs and chicks predated. The number of breeding pairs is thus maintained by immigration but nothing fledges.

GOOD NEWS FROM GROUSE MOORS

But there is good news. There are places where curlew, and a host of other ground-nesting birds, are doing really well. Places where they breed with such success that they produce sufficient fledged young to see local populations maintained or increased. These places, which are producing surplus curlew that could repopulate the landscape, have a technical name. They are called grouse moors.

To say that the RSPB does not like this fact is a huge understatement. Its vice-president, Chris Packham, talks dismissively of grouse moors “curlew farming”, and claims that their success on grouse moors is irrelevant. The RSPB itself is also in denial, claiming that grouse moors are ‘industrial landscapes’ devoid of life and biodiversity. The fact that most grouse-moor keepers can see more curlew out of their kitchen window than you can find on the whole of the 8,000 acres of moorland at the Lake Vyrnwy reserve bothers them not a jot.

The bird gets its name from its ‘cur-lee’ call.

As I said at the outset, it is the success of grouse-moor management that seems to enrage them as much as anything but, to be fair, they probably do not need to worry. Their capacity to play the system has now reached levels not previously seen, even in the conservation industry. The fact that privately funded grouse moors can produce better biodiversity outcomes, and that the RSPB cannot evidence anywhere to compete in terms of curlew conservation, is irrelevant. It can still draw in huge sums of public money on the back of the poor, benighted curlew. The worse it does, the more money it gets. Poor old Curlew Country, one the few curlew projects actually to produce some fledged curlew, can’t get a bean, while RSPB continues to be showered with cash.

The Heritage Lottery Fund’s £3.3 million grant for Lake Vyrnwy was based partly on the impending extinction of the curlew; the same applies to the €7 million for killing stoats on Orkney. But the most striking award has just come to light: the EU LIFE fund is gifting the RSPB the lion’s share of €4.6 million for work at five historic curlew locations. As this sum is only about a third of the RSPB’s operating surplus, an unkind person might ask why they didn’t do something earlier, but at least the fortunes of this lovely bird will now improve. They ought to for £4 million plus. The RSPB has been given more money in one hit than it costs to run most conservation charities in their entirety. So what is the target to be achieved by all this money?

The perfect habitat, but without gamekeepers curlew populations are at risk.

Twice as many? Perhaps 200 additional pairs? Three hundred? If it was 400 additional pairs at the end of the project it would be £10,000 a pair. By conservation industry rates a very good deal. Well, no. Not 400 additional pairs. Not 300 or even 200. How many then? None. The target for an expenditure of more than £4 million is, to quote from their own document, “That the number of pairs at these sites will be at least as high at the end of the project as at the start.”

The RSPB’s English project site is Geltsdale, which, when it was a grouse moor, was alive with curlew but now, sadly, so reduced that apparently only nearly a million pounds can save them. To quote the RSPB’s description of the site, “Geltsdale, which lies in the heart of the Pennine Region, which is by far the most important part of England for curlew.” Would that be the Pennine Region that is one of the most important parts of England for grouse shooting and where any grouse moor can produce more curlew than the RSPB? Well, yes, it would be.

But, as ever, the RSPB need not worry about the obvious fact that a moorland keeper with a bad leg and a fear of the dark could out perform it. It need not worry that it has a record of success with curlew akin to my success at indoor hang gliding. When your network of friends and contacts extends through every grant giving body and no one is too bothered about value for money, nothing matters. For the RSPB, incompetence has its own reward.