Incorporating colours and patterns inspired by the surrounding landscape, estate tweeds are a perfect blend of practicality, exclusivity and tradition writes Harry Wallop

Shooting can attract the flashier type: those who arrive by helicopter, who shoot with a Fabbri Titanium gun and wear £350 alpaca socks. But if you really want to impress your host – or indeed your guests – there’s a classier way of showing off: turn up wearing your own estate tweeds.

What are estate tweeds?

This is tweed you can’t buy in a shop, even swanky ones in Mayfair. This is tweed that either you have inherited or has been designed very specifically for you and, usually, your Scottish estate. “This is bespoke, upon bespoke,” says Campbell Carey, 50, the creative director of Huntsman, one of Savile Row’s smarter tailoring companies, which has dressed everyone from Edward VII and George V to Clark Gable and Brad Pitt. It is also famous for its tweed.

Carey, from Ayrshire, says: “I get clients who say: ‘I want you to make me something none of my buddies can have or get.’ Once you get to that level of wealth the term bespoke is just bandied about and becomes meaningless. However, a Huntsman suit made with your own estate tweed? That is extra, extra exclusivity.”

It certainly is. But it’ll cost you: the Huntsman ‘Tweed Experience’ starts at £18,000, though alongside your bolt (60 metres) of unique tweed you do get a jacket thrown in.

Any good tailor will offer hundreds of different tweeds – from the famous Harris tweed, which has to be spun and woven on the Outer Hebrides, to Donegal tweed and Saxony tweed – all made slightly differently and all coming in a dizzying array of patterns and colours. But none of these are estate tweeds, which are the origin of most tweeds worn today.

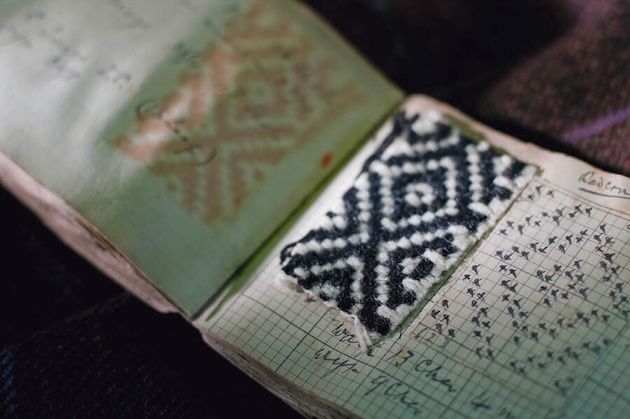

Lovat Mill has nearly 300 different estate tweeds on its books and designs around 10 to 20 new ones each year

History of estate tweeds

The history of estate tweeds is, in some ways, the history of Scotland following the Highland Clearances and the arrival first of sheep, replacing black cattle, and then the English aristocracy, replacing clan chiefs. The ancient rulers of Scotland had a tradition of giving their retainers clothing made out of their clan tartan. New owners wanted to follow this example but had no right to wear a tartan so had to find some other cloth. They chose the simple ‘shepherd check’, a black-and-white criss-cross pattern made from rough wool and used by those tending sheep.

The earliest known example is from the Glenfeshie estate, in the Cairngorms, which in the 1830s was rented by General Balfour of Balbirnie. His daughter took the shepherd check and added a red overcheck – for every seven lines of black or white there’s a red line. She then dressed all the gillies and keepers in that fabric: the Glenfeshie estate tweed.

While a tartan is associated with a clan or family – anyone with the surname Mac- Donald can wear MacDonald tartan – estate tweeds (designed to replicate colours associated with the estate) can only be worn by those who own or work on that particular estate. It is rooted in geography. As the Earl Cawdor, whose fawn tweed mirrors the moorland of the famous Macbeth landscape of his estate, tells me: “Tweeds from neighbouring estates are readily recognisable within a fairly small catchment, not unlike the away strip of a rival football team.”

Some families guard their tweed jealously, laying down rules as to who can and who can not wear it. As a young teen I would spend the Glorious Twelfth at Glenquaich, near Dunkeld, owned by Charles, 8th Earl Cadogan. He and the keepers wore the blue-grey Snaigow tweed, named after another Cadogan estate a few miles away. He insisted only male Cadogans over the age of 18 (and staff) were allowed to wear it: a restriction even his own family thought draconian. Fewer than a dozen of the 120 staff on the Atholl estate – just the keepers, who still use ponies for stalking – can wear the bluebrown check pattern. When they retire or move jobs (unless they are long-serving) they have to hand their tweed back.

I grew up with what I thought of as a ‘family tweed’, Guisachan, a rather natty cream, black and yellow tweed named after an estate in Glen Affric; my father had some plus-twos and – implausibly – a Beatles-style shooting jacket (with zips) in the late 1960s made with the very last of the fabric. However, the Wallop family owned the estate for less than 30 years, between 1908 and 1935, after Great Uncle Redbeard (as we call him in the family) disastrously sold a valuable tract of farmland in Devon to indulge his passion for stalking. A fortune was lost but a tweed was inherited from previous owner Lord Tweedmouth, the man who first bred golden retrievers (which might explain the blonde hue to the tweed). In theory, the current owners of the land, the Forestry Commission, have rights to the tweed but there are no strict rules and – unlike tartans – no official registry, just gentlemen’s agreements.

Edward Bradford, 44, has recently taken over Kincardine Castle in Aberdeenshire from his father. Though the shooting has been handed over to a syndicate – and there are no keepers to kit out – Bradford does have “the full works: everything from a kilt to a hat” in the Kincardine tweed, designed by his grandfather. It has a brown base with a grass-green horizontal stripe and orange and blue verticals. “I think it’s a good one,” he says proudly. But he adds that if he was forced to sell the estate, he’d be tempted to leave the bolt of fabric for the new owner: “It is very much an estate tweed, it’s definitely not mine.”

Of course, you may not like the tweed that comes with the estate, in which case you can start all over again by designing a new one. That’s what the 10th Duke of Atholl did after inheriting Blair Castle in 1957, creating an entirely new design. If you can’t afford Huntsman, you can go straight to a mill. Most charge about £50 a metre but insist on a minimum order of a bolt, so the starting price is £3,000 before any fees for actually designing the fabric, let alone making a suit or shooting breeks.

Lovat Mill’s archive dates back to the late 1890s

From ‘tweel’ to tweed

The Lovat Mill claims to be the oldest surviving tweed mill, still weaving in Hawick in the Borders – a town responsible for the word ‘tweed’ itself. A London cloth merchant misread a label marked ‘tweel’, then a popular rough cloth made in Hawick, and thought it said ‘tweed’ and used this term when ordering the next batch. The weavers of Hawick decided this mistake was good branding and embraced it.

Lovat has 280 different estate tweeds on its books but will not divulge any clients. “It’s quite a private part of our business,” says James Fleming, the managing director. “If we’ve developed a tweed for an estate, we wouldn’t make that for anybody else. That’s their pattern, and that’s the privacy of it.”

To this day, Lovat designs around 10 to 20 estate tweeds a year, and not just for new owners. “If somebody, for instance, doesn’t like Grandpa’s tweed and wants to change it,” says Fleming, a self-confessed “tweed geek”. After an initial consultation with the owner, “we might then visit the estate with our designers to take inspiration from the colours of the estate, whether that be the stone in the house or the buildings, a colour of paint used on the estate or perhaps the colours of flowers at certain times of year”.

Fleming explains: “We’re looking for identity colours, be it the greys of a Grampian estate versus the red bracken of an Island estate. All these colours are extremely important because they represent the estate but also from the principle of camouflage as well. Ultimately, if the gillies and gamekeepers are going to be wearing it, they want to blend in with the flora and fauna.”

Many Lovat archive patterns provide inspiration for modern designs

Colours and camouflage

The most famous camouflage shade is the Lovat mixture – confusingly, nothing to do with the Lovat Mill. This beautiful greenblue shade of tweed came about when Lord Lovat in the 1840s was looking across Loch Morar and remarked to his wife how the primroses and bluebells, which were in full bloom, blended in with the hill, the white sands of the loch shore, the bracken and the birch trees. That mix of colours – the perfect encapsulation of a Highland spring day – was then translated into cloth.

How? Luckily, Johnstons of Elgin, one of the largest mills to still make estate tweeds, has a good archive and the records show that the original Lovat mixture is a ‘melange’, where you mix different colours into one yarn: in this case 38 parts light blue, 16 parts bright yellow, 22 chrome yellow, 12 parts dark yellow-brown and 12 parts white.

“It’s a blending process,” explains Louise Sullivan, the design manager for apparel, cloth and home at Johnstons of Elgin, showing me tufts of five very differently dyed wools. “All those different fibres go into a blending bin and get blended together and put through a carding machine.” This machine cleans and blends loose fibres into something called a roving that is then twisted into thread: “Your final thread ready for weaving will have all those different colours.”

That is just one thread, incorporating five different colours. “If you twist that with another melange, that’s 10 different colours within one yarn,” she adds.

Then there are all the different patterns. The most basic (after the shepherd’s check) is what’s called ‘gun club’ check. This is a simple check with three colours (a light, medium and dark) and so called because Coigach estate tweed – a black and brickbrown check on a cream base – was adopted by a particular American gun club. The records are vague as to the exact gun club, but it’s likely to be the one in New York or Baltimore.

One story is that they couldn’t pronounce Coigach (‘Coo-yiff’) so they called it after their own American institution. So now any three-colour equal-sized square check tends to be called gun club or gun club check. The Cawdor tweed, for instance, is a gun club, so too the Atholl tweed.

Estate tweeds by Johnstons of Elgin. Clockwise, from top left: Iowan family tweed; Lovat mixture; Balmoral Glenurquhart; Balmoral tweed; Coigach (or gun club) tweed; Guisachan tweed

Royal patterns

The other famous pattern is the Glenurquhart, now spotted in fashion houses around the world, from Milan to Paris, but designed for the Countess of Seaford in 1840. It is a complex combination of thick and thin black and white both up the warp and along the weft, giving the impression of smoky effect. The Prince of Wales check is a version of a Glenurquhart.

The Royal Family has two separate estate tweeds: the basic Balmoral tweed for gamekeepers, gillies and staff; and the Balmoral Glenurquhart, reserved just for the Royals. Johnstons of Elgin holds the Royal Warrant and makes this – designed by Prince Albert back in the 1850s – along with plenty of more modern estate tweeds.

But while most estate tweeds are rooted in tradition and the landscape of Scotland, there’s nothing to stop owners being a bit more playful. In recent years, Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen, the grandson of the Lego founder, who owns three separate estates in Scotland, had an estate tweed designed with a Lovat base and a thin windowpane overlay, with bright yellow, bright blue, bright red and white stripes – representing the colour of Lego bricks. A source tells me: “It actually works really well.”

Campbell Carey at Huntsman says one of the most fun tweeds he has just helped design was for an Iowan family who have made a fortune from construction: “They turned up in our New York shop with bags of sand and rock from their quarry, and asked us to recreate the red and yellow Studebaker truck their grandfather drove and the rocks from his quarry.” The tweed sounds alarming but when Carey shows me the finished product, it’s a beautiful cloth: a houndstooth with subtle red and yellow overcheck that would look as good on a moor in Argyllshire as on a turkey shoot in Lee County, Iowa. “It’s an amazing heirloom. An estate tweed can go on forever,” says Carey.

One thing is certain. Estate tweeds, with their rich history and potential future, are anything but boring and tweedy.