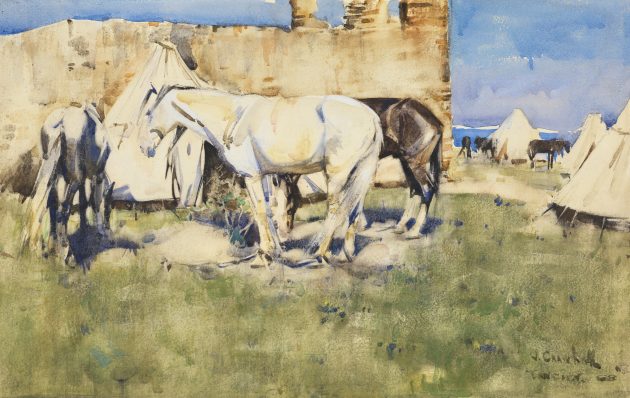

Eschewing the sentimentality of earlier Victorian painters, Jospeh Crawhall created masterpieces of observation, says Janet Menzies

Eschewing the sentimentality of earlier Victorian painters, Jospeh Crawhall created masterpieces of observation. Janet Menzies takes a look at this iconic sporting artist.

SPORTING ARTIST: JOSEPH CRAWHALL

The ambition of every creative agent is one day to find a genre-buster: the new novel that breaks out of the narrow confines of chick lit to be, in fact, literary fiction, or the artist whose work explores traditional subjects from an installation art perspective. Sporting art has majored on genre-busting artists from the beginning, with Stubbs challenging the 18th-century view that horses were a fit subject only for inn signs, right up to Damien Hirst, whose Mother and Child Divided appeared in his Natural History collection. So Joseph Crawhall’s late 19th-century work as part of the Glasgow Boys group is following a heritage of familiar sporting scenes painted in the most innovative way.

The Glasgow Boys came together in the early 1880s as they shared their dissatisfaction with the Victorian highly posed, photographic depiction of sentimental subjects. Instead, the Glasgow Boys were influenced by Dutch and French art to paint rural subjects directly from nature, en plein air, as the Impressionists did. Their work became the take-off point for Scottish modernism, and Crawhall’s paintings of hunting and sporting scenes were at the heart of the movement.

Crawhall was from Northumberland, but met the Glasgow Boys through his sister, Judith, who was married to the brother of EA Walton, one of the movement’s founders. This was the genre-busting moment. Dr Jo Meacock, curator of British art at Glasgow Museums, explains: “He grew up with a really sporting family. His grandfather was a keen huntsman and they hunted and rode together. Crawhall often joked, ‘Providence would have placed four legs on man had he intended him to walk.’ His unique attribute came from really close observation. He was one of the first to paint the horse’s movement accurately and get the strides right. There is an authenticity about his work. Although he didn’t paint on the spot like the Impressionists, he would watch for hours and developed his own system to remember the scenes.”

Enjoying a Crawhall hunting scene today, it seems impossible that it was painted more than a century ago. The Meet features your own hunter – a little bit cobby maybe, but good across country, clipped-out with the head left on just as we would now. The dappled light and flowing brushstrokes must surely have influenced Sir Alfred Munnings, and in old age, Munnings wrote a foreword to Adrian Bury’s Joseph Crawhall: The Man and the Artist. In turn, it is likely that Crawhall was influenced by Edgar Degas, whose horse-racing art feels so contemporary now. Meacock speculates: “It is interesting to connect Crawhall with Degas. I think Crawhall would have known Degas’ work. And like Degas, Crawhall had access to photographs of horses in movement – which we know influenced Degas. There are also similarities in the way they both show the natural movement of the horse, often with a modern composition which frames just an element of the scene.”

Crawhall’s contemporaries admired him from the start. Fellow Glasgow Boy Sir John Lavery wrote: “In a few lines he could sketch an animal, making it more recognisable than the most candid camera could do. If he did a pack of hounds, the huntsman would be able to recognise every single one, even when it was indicated in half a dozen marks on linen paper.” Another member of the group, Sir James Guthrie, was quoted after Crawhall’s death, saying: “He has always been a consummate artist, the perfection of the means for the end he had in view, the fineness of his instinct for form, colour and design.” But it was his close friend George Denholm Armour’s comments that Crawhall would probably have valued most. The two artists both loved horses and equestrian sport, and ran a stud together for a while. They would often spend time in Tangier, and Armour said: “He was a beautiful natural horseman, and in Tangier was our champion jockey.”

Crawhall has certainly been an influencer of modern equestrian art, yet his name isn’t as instantly recognisable as many sporting artists of the 19th and 20th centuries. According to Meacock, this is because Crawhall was in some ways the victim of his own success, attracting two major Scottish collectors, William Coats and William Burrell. Meacock explains: “Burrell especially was really quite obsessive in his interest in Crawhall and he would snap up the works at every opportunity – including when much of the Coats collection later came up for sale. And Burrell hung on to them as well. He was often happy to sell paintings if he was offered a good price, but not a Crawhall. So now we have about 150 works here in the Burrell Collection at Glasgow Museums and it is the most extensive in the world.”

View Joseph Crawhall’s work at the Burrell Collection, Pollok Country Park, Glasgow G43 1AT.

Dr Jo Meacock’s book, Introducing Joseph Crawhall, is on sale now. For more information, visit: burrellcollection.com