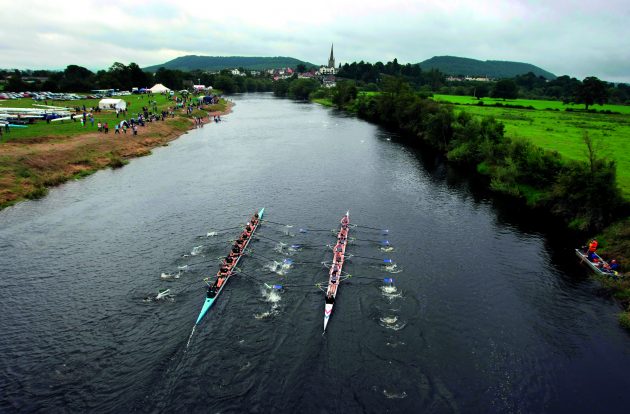

Multi-lane lakes may level the playing field for top rowers but in Britain, when regatta season rolls around, rivers reign supreme

Rowing legend Sir Steve Redgrave says of Henley Royal Regatta (HRR): “It’s a battle for crews to get to the start, it’s a battle to warm up, but most rowers I talk to around the world want to race there at least once. People love it for the atmosphere as well as the tradition. It’s the nearest thing that rowers ever get to competing in a stadium.”

It may be the most famous rowing contest in the world, but as a two-lane race on moving water it’s also a complete contradiction for any elite oarsman, whose important events are all otherwise run on multi-lane rowing lakes. (Read The Field’s guide to picnics 2025.)

What sets Henley apart is the atmosphere, unmatched even at an Olympic Games, points out Sir Steve. “Matthew [Pinsent, Redgrave’s pairs partner of many years] and I used to boat in deathly silence at the Barcelona Olympics,” he remembers. “It was just us and our coach. There was no real noise of any sort until the last 500m. At Henley it’s a wall of noise right from the start – spectators can almost reach out and touch the oars at places on the Berkshire station – and many rowers have never experienced that before.”

Beloved river regattas

The qualities that give Henley its star appeal are what make our river regattas so beloved all around Britain: the proximity of crews to a leafy riverbank packed with vocal, local people; rowers dodging swans, reeds and steamboats; and a happy bankside blend of picnickers, boat trailers, food tents, coffee stands and club colours. (Read The Field’s picnic recipes here.)

Britain’s rowing heritage – and prowess – stems from the fact so many of our towns and universities grew up on rivers. As boat clubs sprang up in places such as Staines, York, Stratford and elsewhere, the sport became visible and accessible. Many great European rivers, on the other hand, are fed by the Alps, points out Sir Steve, making them less suitable for summer rowing, so the sport there is more centred on purpose-built or natural lakes.

NOT SO STRAIGHT AND NARROW

While few places in Britain can offer 2,000m of straight river like Henley, Britain’s boat clubs have not let that stop them. Consider Sudbury Regatta in Suffolk, which runs ‘long’ races over 600m and sprint races over just 350m. “Ours is the ultimate impractical setting for classic, fair side-by-side racing,” agrees a spokesperson, cheerfully. “We have a staggered start because there’s a substantial bend halfway through our course, and a small one at the finish that catches everyone out as the ‘red mist’ descends.” Nonetheless the regatta has only grown in popularity, partly because there’s a fun festival feel to it, with parent-and-child racing, a jazz band, a hog roast and home-made ice cream.

Durham Regatta, Britain’s second oldest after Chester Regatta, also draws sizeable crowds and races over two different length courses. The long course, over 1,100m, is reserved for the regatta’s biggest events, such as the Grand Challenge Cup, following the ancient route of the annual procession of boats to commemorate Wellington’s victory at Waterloo, from which the regatta grew. It requires crews to navigate through the steep-sided gorge in the centre of Durham and squeeze through Elvet Bridge, built in the 1100s with no thought of coxed fours in mind. “It’s the rowing equivalent of going round Cheltenham – lots of tricky obstacles,” says a regatta spokesperson. “You don’t know whether to close your eyes or duck your head as you go through it. The coxing is absolutely key.”

But the gold medal for consistent determination should perhaps go to Ross Regatta, which takes place each August bank holiday. Described by Tim Davies of Ross Rowing Club, as “a warm, friendly, old-school regatta, started in 1876 and much better than Henley”, it thrives despite a gamut of topographical quirks. “It’s windy as a snake,” agrees Davies. “We have a staggered start and finish, and we buoy off the course to stop boats hitting rocks, which makes it rather narrow in places.”

The Wye – as any salmon fisherman will tell you – is prone to much variation in water levels and after a dry summer can be barely knee-deep. This actually forced the regatta’s cancellation in 2022, to much disappointment. Regatta weekend is a highlight of Ross-on-Wye’s year. “People from the town come down, and all the pubs enter crews in the dragon boat racing categories. We try to make it as town-orientated as possible because rowing has this stigma of being an upper-class sport and it really isn’t,” says Davies.

By the 1970s, however, purpose-built watersport centres such as Holme Pierrepont in Nottingham, London Docklands and Eton Dorney began changing the landscape. Offering multi-lane racing over 1,500m to 2,000m, they enable rowers to have a pseudo-international experience, and allow far more crews to race per day. This was useful as rowing grew more popular with the advent of Lottery funding, particularly among juniors, students and seniors. Pressure on rivers has also increased – who hasn’t noticed growing numbers of wild swimmers and the influx of paddleboarders?

River regattas vs watersport centres

Long-established river regattas, including London Metropolitan, Marlow and Wallingford, upped and moved to multi-lane courses such as London Docklands and Dorney. Nottingham’s National Watersports Centre at Holme Pierrepont hoovered up many of the traditional old regattas run on the Trent. Marlow’s move to Dorney caused a huge furore but its pre-Henley dates meant droves of crews, including internationals, wanted a last chance to qualify for HRR and to race over a similar distance.

“We’d had a regatta since 1850 – the town was up in arms,” says a spokesman. “We understand the rowing reasons for going to Dorney, but you can’t just denude a town of its regatta.” The solution was to start a second regatta, now called Marlow Town Regatta, to which local clubs send their less high-powered crews. Marlow Town uses a 1,000m stretch of the Thames wide enough to race boats three abreast (“but we still have two bends”). Despite the superior brawn doing battle at Marlow Regatta at Dorney, the spokesperson points out: “Marlow Town gets 5,000 spectators; the one at Dorney has virtually none.” This is a point endorsed by Sir Steve Redgrave: “At Henley, the sport has always been a part of the community. As soon as you go to a multi-lane, races move away from that.”

While rowing lakes are indispensable for running vast events such as the National Schools’ Regatta, and no one disputes they are the fairest way to split quite evenly paced crews, they can have their own problems too. They can often have more wind than a river and can produce surprisingly dull, processional races, with a mass of crews trailing the quickest. “A river is not as reliably fair as a rowing lake but, most of the time, the verdict between crews is not 6in,” points out Helena Smalman- Smith of Thames Ditton Regatta.

English chaotic charm

“Multi-lane is what it’s about when the margins get tighter but coping with river cruisers, waterfowl, staggered starts, distracting girlfriends on the bank… it’s all part of rowing’s folklore, and a quintessential English chaotic charm is lost when you move to multi-lanes,” adds Ashton Shuttleworth. He rowed for years to a high level but nothing for him will ever top winning Henley’s Temple Challenge Cup with Imperial College in 1998.

Rowing umpire Andrew Blit also sees purpose-built rowing courses as a necessary evil. “It’s a completely different dynamic doing side-by-side rowing compared with multi-lane. It denatures the experience. On a river you take your chances with the stream, the bends, the conditions and debris – it more accurately represents the roots of our sport.”

Sir Steve may have won countless championship medals on lakes but he flies the flag for river rowing too, as well he might as a Marlow man himself. “I would have hated it if I’d had to do all my training just on a lake, but you only know what you know. Henley brings a credibility to river racing, and the fact that we row mostly on rivers in this country is never going to change.”

Brilliant, bonkers regatta

Chester Regatta, Britain’s oldest, urges crews on the meadow side to look out for a protruding tree 150m down the course, to be prepared “to take evasive action” around large pleasure boats as necessary, and to “be aware of a ferry for foot passengers” 100m upstream of the finish.

Llandaff and Durham regattas (for the long course) both have weirs soon after the finish. Hold hard once you’ve finished racing or “you’re off to Sunderland”, says a Durham Regatta spokesperson.

Ross Regatta’s winding course has a staggered start and finish, is rather narrow in places and can become exceedingly shallow. Apart from that, it’s perfect…

Twickenham and Richmond regattas use the same course, which also has a staggered start and a late bend on the course that can quickly crush a crew’s sense of impending victory.

Bradford Amateur Rowing Club’s regattas on the River Aire win the nomination of City of Sheffield rower and former captain Cat McDougall for triumphing over adversity. “It’s a beautiful, picturesque little regatta with lots of capsizing and crashing,” she says. They’re run on a tiny stretch of river only about 600m long, with no possibility of warming up on the water before racing. Bradford’s annual War of the Roses regatta is an invitational for veteran rowers from across the north; entry fees include a plate of curry.

Thames Ditton falls early in the year and for many young rowers is their first ever regatta. This worries households on the island by the start. “Most have a motorboat moored outside and don’t like children hitting them,” explains regatta secretary Helena Smalman- Smith. The Club’s solution has been to invent a floating official they call ‘The Sheepdog’ to take over coxing duties for any young steersman who looks like a rabbit in the headlights.

This article was originally published in 2023 and has been updated.