The Field was published throughout the First World War, here is unique archive material from the time. In the countryside we were bloodIed but unbowed by WW1

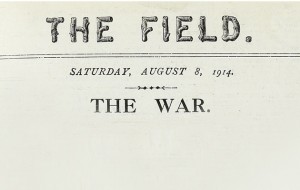

THE FIRST LEADER PRINTED IN THE FIELD DURING WW1

“It has been difficult to realise that life in England must, after all, in its broad lines, go on much the same in spite of the storm that is being pitilessly sown across the Channel and the North Sea… We may remember that in the hour of our peril our domestic quarrels are forgotten, and the sons of our Dominions over seas are hastening to stand shoulder to shoulder in our lines in the fight that is to fix the future of all our generations to come. With that thought before us, we can keep calm even if we have to face an enemy within these shores; for we can at any rate determine that very few of the invaders shall get home again. And there is not a man or woman who cannot take a part in what is the privilege, the duty, the stern necessity of all. “They also serve who only stand and wait.” That is often the hardest task of all. It is always the woman’s. Let us remember that, and help them in their time of need until their men might come home again. And for the rest, let us do with all our might that task which happens to be set before us, whatever it may be. For life, as has been said, must go on, in its broad lines, in every city and hamlet in this realm essentially unchanged, in spite of all the outside turmoil. Those who are not in the actual fighting line (and they will grow fewer every week) have to keep the ordinary life of the nation in steady continuance. It will be not only legitimate and natural, but it will be right that they should keep in sound health of mind and body by reasonable recreation of every ordinary kind. Sport has made many of our best sailors and soldiers better in their warlike trade. Sport can also keep fit and ready those who may in the end

“It has been difficult to realise that life in England must, after all, in its broad lines, go on much the same in spite of the storm that is being pitilessly sown across the Channel and the North Sea… We may remember that in the hour of our peril our domestic quarrels are forgotten, and the sons of our Dominions over seas are hastening to stand shoulder to shoulder in our lines in the fight that is to fix the future of all our generations to come. With that thought before us, we can keep calm even if we have to face an enemy within these shores; for we can at any rate determine that very few of the invaders shall get home again. And there is not a man or woman who cannot take a part in what is the privilege, the duty, the stern necessity of all. “They also serve who only stand and wait.” That is often the hardest task of all. It is always the woman’s. Let us remember that, and help them in their time of need until their men might come home again. And for the rest, let us do with all our might that task which happens to be set before us, whatever it may be. For life, as has been said, must go on, in its broad lines, in every city and hamlet in this realm essentially unchanged, in spite of all the outside turmoil. Those who are not in the actual fighting line (and they will grow fewer every week) have to keep the ordinary life of the nation in steady continuance. It will be not only legitimate and natural, but it will be right that they should keep in sound health of mind and body by reasonable recreation of every ordinary kind. Sport has made many of our best sailors and soldiers better in their warlike trade. Sport can also keep fit and ready those who may in the end

be either called into the last desperate stand or ordained to supervise incessantly those wheels of life and industry which no community can afford to let run down. We hope, therefore, that as little sport as possible will be abandoned in these islands during the bitter weeks to come; for it will help not only the body but the mind. The only nations which can hope to survive the crucial test will be those whose citizens can preserve unswerving courage, patient resolution, and an infinite trust that God will shield the Right.”

THE COUNTRY ADAPTS

Great Britain had been at war for only four days when the words above appeared in The Field’s leader column but they were to set the tone for the magazine and, one might say, the nation during what was to develop into the First World War. However, it would grind on for four years rather than the painfully optimistic “weeks to come” referred to more often in the early stages.

Life in the British countryside was to be changed ineradicably and yet remain miraculously constant in the way that people went about their business in determined fashion, cocking a snook at “Prussia’s aggressiveness” by maintaining a sporting life at home and interest abroad that belied the cost being extracted to achieve our aims in battle and ultimately secure an Allied victory.

Life in town didn’t survive unaltered, either. Going about one’s business in Kennington one could see the Oval taken over by the Artillery, gun horses grazing on the hallowed turf, but we reassured cricket fans that the pitch and field had been carefully railed in so there was no danger of hoof damage to the square leg. On Epsom Downs there was the comic spectacle of semaphore training. And in St James’s Park one would be as likely to come across the Grenadier Guards’ transport section as a dog walker.

WW1 CAVALRY

The cavalry have always been photogenic and we were able to illustrate “what the men can teach their animals to do” at the Neveravon School, set up to produce expert riders and horsemasters and teaching techniques that will be familiar to any Pony Club member today such as learning to “jump without reins or stirrups, come down steep banks…” It was thought to be “a fine institution with good grounds” where, “it is considered that if a horse’s natural paces are properly developed and he becomes a first-rate charger and hunter, the practical objects of horse training for war have been achieved”.

Horses, still a mainstay of agriculture and, of course, sporting life, were soon in great demand but rather than bewailing their loss as remounts and to the front we were able to congratulate ourselves on producing perfect chargers and extol the relative merits of hunters and polo ponies for the job. Both exemplary. “The badly bred horse, short of quality and inclined to be common, is of no use whatever in a cavalry charge, for he lacks the courage and pace of the high-mettled hunter, as also the lasting power. It is well known that a hunter in good condition will do his fifty or sixty miles a day with very little trouble to himself, and the average working day in a hunter’s life involves not only a very considerable amount of fast work, but the jumping of a great number of fences. Here, then is the material from which good cavalry mounts are made.”

But do not imagine that The Field or the nation developed a myopic view of the world, seeing life only through the prism of war. We had waved Sir Ernest Shackleton off on his ill-fated but heroic expedition as war was breaking out and maintained a weather eye on the world that was, like Shackleton’s team, not in combat in Europe.

A record tuna of 710lb reached our pages from Nova Scotia, brought to boat with a mere 200yd of line on Mr Mitchell’s rod after a battle of eight and a quarter hours. “After the first rush which ran out about 200 yards, he held it on less than 75 yards, and for the last three hours the struggle was on about 20 yards. It towed his skiff some eight miles off shore, and then about four back to land before it was gaf-fed.” For obvious reasons our correspondent was keen to know Mitchell’s fighting weight.

ASTONISHING RETRIEVE

Gundogs have ever been fascinating to sportsmen and I would challenge any modern reader to match the “Plucky Retriever” who had his battle on Skye and was triumphant in retrieving a seal of 6st 11lb. “[The shot seal] was not much hurt and rushed into the water, the dog followed it and caught hold, both went down together in the sea. On re-appearing the seal was swimming fast but Cuchellin rushed after it and caught hold, and they sank again completely. This was repeated five times. The fifth time they came to the surface Cuchellin had kept his grip on the back of the seal’s neck and proceeded to swim ashore with a paw on either side of its body.” Submariner, nil; outgunned Scots sailor, a very definite 1.

On a more practical front, readers advocated “wild food”, the recommendations to eat seaweed, rabbits and game in general through tough times sounding very much like cookery writers today. Other topics included donation of blankets (by boat owners) and binoculars (by stalkers) to our armed forces and the merits of arming sentries with shotguns – apparently the use of No 4 or No 5 shot was “absurd apart from at very close range”. A pressing concern for one elderly reader was to maintain his fitness and riding muscles without a horse.

In the issue of 22 August 1914 The Field announced in the Farm pages that, “In a pathetic paragraph on its front page the Journal d’Agriculture Pratique (an excellent farmers’ paper printed in Paris) announces that it is obliged to cease publication. ‘Our whole staff… has gone to his post in battle to defend his country. Our subscribers will therefore appreciate the circumstances which necessitate our decision to stop the paper for the time being; and they will, we are sure, associate themselves with our prayer for the success of the French arms.’ Every journalist and agriculturalist in England will hope that prayer may speedily be granted.”

CONTINUOUS PUBLICATION

The Field was able to continue publication without interruption throughout the conflict. Our then weekly recipe of sports (field and recreational), farming, agriculture, aeronautics, travel and the natural world grew to include the armed struggle. Table-thumping leader columns and an important historic record of the progress of the war are here but, delightfully, there is room for important issues of the day such as how the fish are moving on the Itchen or the feeding value of bracken.

Business very much as usual then, except, of course, it wasn’t. In the first December of peace we announced with dismay that “In 1919 there will be a new and hitherto un-known generation of rowers who have never been to Henley Royal Regatta.” Well, there had been a war on.