Georgea Blakey’s striking collages resonate with associations that are both powerful and personal, discovers Janet Menzies

At the end of a British winter it is hard to associate our dogs and horses with glamour, so the work of Georgea Blakey is like a ray of sunshine beaming on to the general bog of muddy dog and wet tweed. Perhaps this is because Blakey has spent much of her time in the jet-set polo-playing world, which seems to revolve around perpetual summer.

Brought up as a horse-mad child in a family with numerous dogs, Blakey remembers: “I really wanted to take a year out and travel. I loved polo, so I went to the polo grounds and did drawings of the patrons’ ponies for £100 each. Pretty soon I had £600, which was what I needed to buy a ticket to Argentina. So there I was, only 19, living out in Argentina on my own with a bunch of gauchos and playing polo. I got a scholarship from the Hurlingham Polo Association and became a groom/player, which was quite difficult in those days, and as a girl you have to work harder and play tougher. You have to tack up more than 20 horses for the high-goal players you are grooming for but, when you are playing, there is no one to groom for you. And you can’t afford more than one saddle, so you have to change your tack from pony to pony in the two minutes between chukkas, which doesn’t leave much opportunity for those amazing leaps across from pony to pony.”

It did leave Blakey physically somewhat broken since a rare bone condition meant she didn’t heal from the knocks inherent in the sport. Eventually her parents felt it was time for Blakey to give up polo in favour of a more conventional career. But rather than the reliable fallbacks of accountancy or personnel, Blakey went for the option of becoming a professional artist, commenting wryly: “It’s not as if art is so much more of a safe career choice than polo.”

It turned out to be a sensible move for Blakey, who explains: “My painting was a great help because it meant that wherever I travelled, I could paint for my supper. One hundred per cent my polo helped with my contacts to find commissions. I met all these incredible polo patrons,” she says, using the Spanish inflexion of patron. “These are the wealthy and influential people who can afford to play polo and fund it. And they all had dogs they wanted me to paint.”

Blakey was soon in demand to paint traditional dog portraits. “I remember in Palm Beach, I was painting so many dogs, and there was one called Romulus who had lost his eye in a fight with an alligator. A portrait takes a minimum of four weeks to complete – you are using a brush the size of an eyelash. You get extremely close to the dog’s personality and I take time to create layers to reveal the nature of the dog.” Blakey points out that many gundog breeds have double coats, and she wants to show that undercoat coming through.

It was this quest for a multidimensional portrait that first led her into collage. She recalls: “The first collage I did was of a French bulldog whose owner was in the fashion world. It is traditional in portraiture to include elements in the finished painting that reflect the client’s passions, so I made the dog’s portrait up out of fashion labels. It is a step on from capturing the dog’s coat; I want to create an animal’s fur and skin as a tapestry of images.”

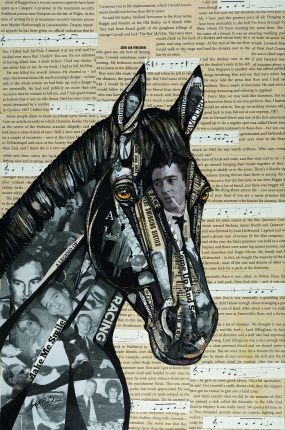

Blakey is often playful with her imagery. A labrador retriever is made up of Bombay Sapphire gin labels and the work called Gin Lab. Another collage of a fox-red labrador is called Best Bud and of course made of Budweiser beer labels. When it comes to her equestrian collages, Blakey’s punning expresses something rather more complex. She explains: “The horses’ names are important. When an owner chooses a horse’s name, they have to think of one that expresses something for themselves as well as for the public. It’s no coincidence that so many racegoers bet on a horse because of its name.”

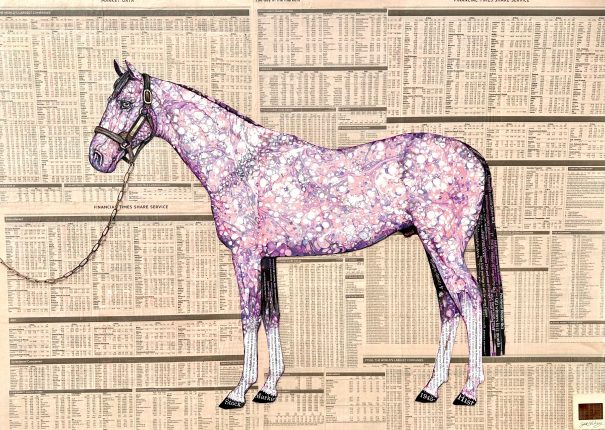

So Cockney Rebel includes images of the Kray Twins and other East London iconography. Bloodstock shows a horse in the sales ring made up from cell pathology images on a background of stock market reports. Blakey reveals: “My mother was a histopathologist and my father was a stockbroker, so this is about me: that is where I come from.” Even more than her conventional portraits, Blakey’s collages resonate with associations that mean something to the viewer as well.

Georgea Blakey’s new exhibition, Carousel, is at the Osborne Studio Gallery, 2 Motcomb Street, London SW1X 8JU from 26 March to 12 April. Instagram: @georgeablakeyart Visit: georgeablakeyart.com