A major new exhibition marks the centenary of artist Norman Thelwell’s birth – and 70 years of his endearing if wilful cartoon creation, Kipper

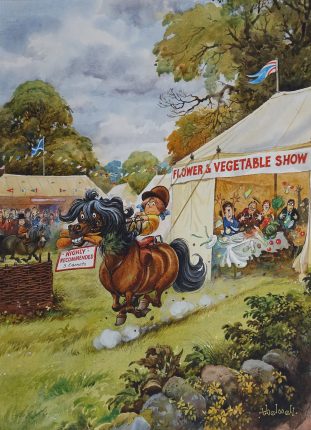

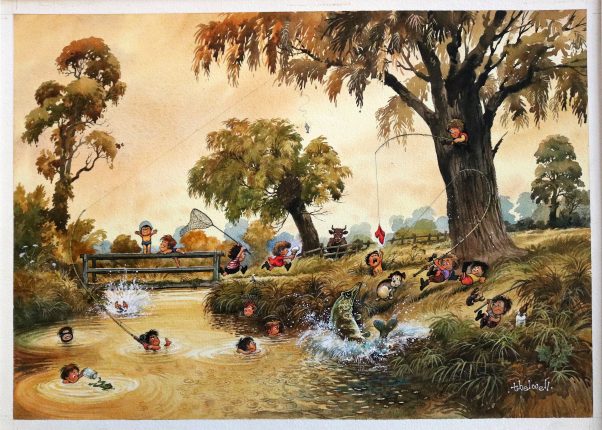

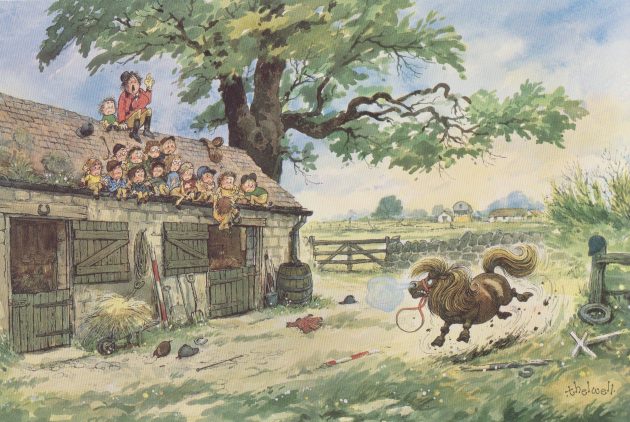

Their ponies were cheerful little shitlands. The children – mainly girls – grew up to manage careers and families and anything else that needed sorting out. The adults ran around picking up cast shoes and fallen riders and the pieces generally. Yet in this joyous chaos of wrecked marquees, ruined lawns and inevitable bramble thickets there is one person missing. Unseen in the cartoons, Norman Thelwell himself is the bemused, non-horsey dad, looking on with fond bafflement at our inexplicable obsession with all things pony.

NORMAN THELWELL – ONE OF THE GREATS

This year is the 100th anniversary of Norman Thelwell’s birth and the 70th birthday of the spherical yet mercurial beast universally recognised as the Thelwell Pony. Thelwell, living in the Midlands at the time with his wife and young son, had started drawing cartoons for Punch magazine in the 1950s. He writes in his autobiography, Wrestling with a Pencil, how he was struck by the daily struggles of two young children with their ponies in the field opposite his studio: ‘As the children got near, the ponies would swing round and present their ample hindquarters and give a few lightning kicks, which the children would sidestep calmly, and they had the head-collars on those animals before they knew what was happening.’ Resilience met reluctance in a relationship of attrition played out in paddocks to this day. No wonder the resulting cartoon for Punch in 1953 struck an instant and universal chord, although Norman Thelwell recalled his surprise at the response: ‘Suddenly I had fan mail. So the editor told me to do a two-page spread on ponies. I was appalled. I thought I’d already squeezed the subject dry.’

CAREER COMMENCEMENT

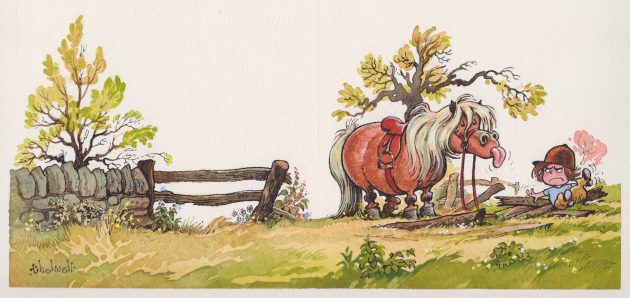

Thelwell’s career as a professional artist had begun during World War I and continued immediately after. He was posted to India and had three cartoons published in the services magazine, Victory, which led to him becoming art editor of a magazine for Indian electrical engineers. Back home in England, Thelwell pursued his love of landscape painting. His son, David, says: “Dad loved drawing the countryside. He didn’t do dramatic, he liked rural scenes. He started painting and then he realised that few people can make a living from that, but cartooning was viable. He was able to combine the landscapes into the cartoons; it was a labour of love. He liked spending time on them and I think that helped make them popular.”

Norman Thelwell’s daughter, Penny, was born at about the same time as her namesake Penelope. She did have a pony and was a member of the Pony Club but her father remained more of an observer than a participant in the stressful life of the Pony Club parent, as Penny recalls: “He said, ‘Don’t expect me to be driving you round the countryside.’” There is a painfully perceptive cartoon of a mother and father desperately trying to squash their daughter and uncooperative pony into a horse trailer, captioned: ‘I’ll be glad when she gets interested in boys.’ That must have something to do with Thelwell’s remark.

For Penny, it is the accuracy of such observations that makes her father’s cartoons lastingly funny. She says: “My father had great imagination; he would spend a lot of time reading and listening to what people were saying. He would read something like The Pony Club Manual, and the caption would be taken from the manual, totally serious, but the drawing illustrating it would be hilarious. He did like to point out our foibles. He was a past master at turning situations on their head. The cartoons are still funny now even when you know what is coming. He went in for detail, and would spend a crazy amount of time on each drawing. He loved the actual physical drawing of each cartoon. And they will live on because each new generation loves them and pointing out the little details.”

In a 1986 documentary for the BBC, Thelwell revealed that detail was indeed vital to the wit of his drawings, telling journalist Bob Wellings: “In this particular situation obviously she [Penelope] has had a terrible disaster, and at this stage we can embellish by putting in details like leaves coming from her hat or great lumps of grass on the back of the pony or various pieces of equipment that she has crashed through.” In the background the film shows Sara and Kate, Thelwell’s two grandchildren, on their own Shetland pony. Thelwell concludes though: “I think they are dangerous at both ends and uncomfortable in the middle. I am not terribly horsey myself but I have occasionally had the misfortune to be mounted and it has been quite a hairy experience on several occasions.”

Norman Thelwell’s true love was trout fishing on chalkstreams, which led him to move the family down to a home in Hampshire where he could fish the Test.

Penny remembers a fairly idyllic childhood: “We lived on the edge of the New Forest. I went to Pony Club and went to camp and all that sort of thing. I wasn’t really very competitive. I was 12 when I got my pony, Tonda. He was a very spirited New Forest pony, not at all fat like a Thelwell. The lady who had him said ‘feed him up’, so we did and he got lots of muscle but he had so much energy he didn’t know what to do with it. He used to fling me about a bit.”

Norman Thelwell may not have seen himself as a typical Pony Club parent but he loved the life of the English countryside. He lived near the National Trust’s Mottisfont estate, and the Trust is currently holding an exhibition of less-well-known aspects of his work, especially his watercolours of local Hampshire landmarks, including Mottisfont itself. Charles Sainsbury-Plaice, of CSP Countryside Greetings, is the main licensee reproducing Thelwell’s work across a wide range of products. “Thelwell was known for his little fat ponies and riders but he also had a serious side to his art and painted many landscapes and seascapes,” he stresses. Sainsbury-Plaice has his own fond memories of the cartoons, explaining: “I loved his images as a child, the annual in the Christmas stocking being a particular highlight. Thelwell also handles country sports in general very well in his work because he always made the human the victim of the joke. His animals always come out on top, and we are the laughable losers. Thelwell was passionate about fly-fishing but his portfolio extends well beyond this into shooting, fishing, hunting, cats, dogs, country houses, sailing and even pollution and the environment.”

Thelwell’s collection of environmental cartoons, The Effluent Society, has just been reissued by Quiller Publishing. The cartoons are even more relevant today than they were when first published in 1971, and Thelwell was particularly proud of it. This has been picked up by director Candida Brady in Blenheim Films’ new adaptation of the Penelope cartoons to be called Merrylegs the Movie, filmed in Snowdonia in Wales – one of Thelwell’s favourite places. Brady says: “Without giving the plot away, the importance of the relationship with the environment is a key element.

“Mr Thelwell has ponies doing things they don’t naturally do. I am a huge animal lover, so everything had to be done properly. In the end, the right pony found me: a little Welsh colt called Harper who hadn’t been handled at all. What concerned me most was the sitting – you often see Penelope’s pony sitting on its haunches while she hugs him. But Harper more or less taught himself to sit, with the help of our trainer,” reveals Brady.

Of all Thelwell’s skills as a cartoonist and artist, his lasting legacy is the creation of Kipper and his equine pals. That first pony, in whose shaggy mane you bury your tear-stained face or whose tiny hooves constantly manage to stand on your toe, plays a part in so many lives. Brady remembers: “I was quite an ill child. The healing powers of horses mean so much, and spending six months in bed reading Thelwell’s books helped me get better.”

Lucy Higginson, former editor of Horse & Hound, fears that Penelope and Kipper are becoming a rarity among the current cohort of elegant young girls in riding leggings and blush-coloured ‘matchy matchy’ outfits. “In the past you started on something shaggy and character-building, and everybody did a bit of everything before working out what to concentrate on,” she says. “Now we see a professional approach from the beginning. But there are still some families for whom that Thelwell-type pony is just what they need. We used to borrow a Dartmoor pony who would come and join us at the barbecue – Charlie the Dartie. You couldn’t swap that experience for anything. It is such a joy having a pony like that and they are very forgiving. There is still a place for the Thelwell and everything it stands for.”

In the seven decades that have passed since Thelwell’s first cartoon appeared in Punch, much has changed superficially and almost nothing in reality. Pony Club children may now wear sweatshirts and leggings but they still have the same unconditional love for their ponies. Whenever we are competing at a three-day event, which generally lasts about a week, I look round at us all camping and drinking in our horse lorries, crying or laughing (usually over the same incident) and I understand: you never grow out of your Thelwell moment.

The Effluent Society is published by Quiller Books, £15.99, quillerpublishing.com 100 Years of Norman Thelwell runs until 7 May at the National Trust’s Mottisfont in Hampshire. Visit: nationaltrust.org.uk/visit/hampshire/mottisfont for more details or call 01794 340757. Merrylegs the Movie is in production with Blenheim Films, blenheimfilms.com