In drawing together the beloved giants of a sport and capturing them in the brushstrokes of the great equine artists of the 18th century, Nichola Eddery has taken on the near impossible and won, writes Janet Menzies

Taking on a commission to paint the racehorse, Frankel, in a deliberate reference to Stubbs was no small feat for Nichola Eddery. But she put herself into training and even though it seemed she was taking on the near impossible, she won, as Janet Menzies discovers.

For more sporting artists, Colin Woolf feels a great responsibility to not just paint the landscape but represent the real countryside within it and Ian MacGillivray finds inspiration in the human relationships with wilderness.

NICHOLA EDDERY

Every contemporary equestrian artist paints in the shadow of the giants: JF Herring, John Wootton, Munnings and, inescapably, Stubbs. How doubly difficult, then, for Nichola Eddery, daughter of the legendary jockey Pat Eddery, to be commissioned to paint the racehorse, Frankel, at the Rubbing House on Newmarket Heath, in a deliberate reference to the Stubbs painting of Gimcrack at the Rubbing House. Just to add a little extra pressure, the project had been a dear wish of Frankel’s trainer, the late Sir Henry Cecil, and had already been started by the well-known racing painter, the late Michael Jeffery, who died around the same time as Cecil.

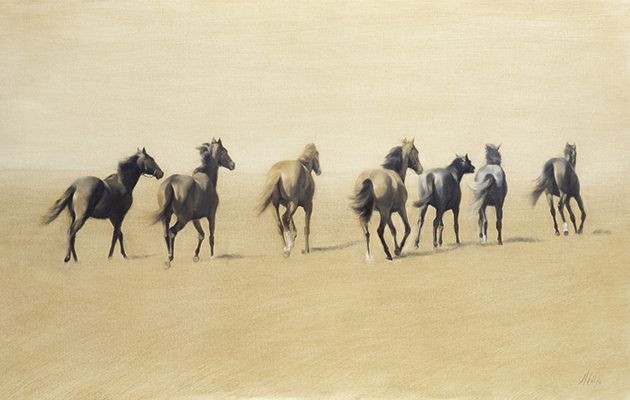

Legends, oil on canvas. Eddery on painting Frankel at the rubbing house: “I was really moved by the story. And, of course, it was in memory of Sir Henry”.

Despite all these challenges – to achieve a work with so much resting on it and the resonances of her own family background in racing – Eddery didn’t refuse at the hurdle.

She says: “I was really moved by the story. And, of course, it was in memory of Sir Henry, such a wonderful trainer. In addition, though, at the time I had been doing a lot of Old Master copies and learning from them, and so making the Frankel piece became an important part of that learning process.”

The project was sponsored by racing enthusiast Peter Merchant, with the understanding that 25% of the profits from the sale of the painting would go to cancer charities; it was Merchant who commissioned Nichola Eddery. He knew immediately he had chosen the right artist. “I remember the first day Nichola went up to Newmarket and she rang me all excited to say that, purely by chance, she’d found herself stood in exactly the same spot as when Stubbs painted his masterpiece.”

FOLLOWING IN FAMOUS FOOTSTEPS

Following in famous footsteps is not something that has been a problem for Eddery. She explains: “When I was little at home Dad had beautiful paintings and I loved the one of Grundy, which was one of my father’s most famous rides. All we children had our portrait painted when we were little. I would have been eight or nine years old and my mum remembers that I was fascinated by the whole process of the painting going on and was always watching the artist working. I can’t remember a time when I didn’t love painting and drawing, as well as being around horses, of course. Then when it came to finishing my A levels and deciding what to do, actually it was not even a choice. There was no question. If I could keep the horses going on in my life, that was the ideal but I knew I wanted to study art seriously.”

My Father on Grundy – the Start of Greatness.

So Eddery put herself into training. First she signed up for the prestigious Charles H Cecil Studios in Florence. “There was a year-long waiting list. So I travelled and painted and rode out racehorses every day. Then I had a chance to study with the Studio Escalier, based in the Loire Valley and in Paris. In Paris, I was actually working in the original studio of the famous 19th-century racing artist Théodore Géricault. We spent the mornings working from life and the afternoons at the Louvre studying and copying Old Masters.

“I had an idea of how I wanted to paint and you have to train properly to acquire the skills you need. I learnt so much from this classical, formal training. I think if you look through art history and at the studios and the great painters, for me to become the painter I wanted to be, I needed to go down that route.”

INDIVIDUAL INSIGHT

So Eddery had a clear vision of where she wanted her work to go but, like so many contemporary equestrian artists, she is aware of how difficult it is to bring individual insight to a genre in which so many great artists have worked. She says: “My vision is evolving as I learn. When I was younger I was mostly attracted to the Renaissance period and then obviously to Stubbs and Munnings. Now, though, I am in love with Degas – and in turn he was influenced by Delacroix. Degas was a genius in so many ways. His composition was so innovative. And to me it is important that he captured something special about how horses react and behave. I feel that when you see a Degas you really get a lot more out of it if you are someone who is around racehorses all the time.”

Nichola Eddery’s work has resonances with not just the equestrian artist giants but also her own family background in racing.

As her work develops, it’s clear that Nichola Eddery will bring her own unique knowledge of the racing world to her art.

Nichola Eddery’s exhibition, Making Paces, is at The Osborne Studio Gallery, 2 Motcomb Street, London SW1, until 3 December. Or visit www.osg.uk.com or www.nicholaeddery.co.uk