As interior design or a record of your sport, trophy heads and more modest examples are striking whether boiled at home or sent to a taxidermist

When news broke that the so-called “Emperor of Exmoor” may have been felled by a “hunter’s bullet”, the indignation voiced by the national media was matched, albeit more discreetly, by a knowing sigh of resignation from Britain’s deerstalking fraternity: the unseemly rumpus must have been caused by an overseas hunter of trophy heads. Trophy-hunting, it is assumed, is something which only Johnny Foreigner would indulge in. The very thought of it seems somehow unBritish.

But think again. Trophies are as much a part of the sporting scene in Britain as they are anywhere else in the world. While we may not place as much emphasis on the medal potential of the head of a stag or buck as some European hunters do, which of us does not wish to bring back from the Highlands a splendid hat-rack to remind us of that lengthy crawl through the peat hags, of a shot well taken and a beast brought down in the heather? We have for centuries decorated our homes with trophies of the chase, be they the antlers of the deer we have taken or the masks and brushes of foxes, hares and other beasts killed by our hounds.

SIZE MATTERS FOR TROPHY HEADS

The point is well made across the pond by Dennis Walrod who, in his book Antlers, comments that, “If anything, Europeans are more obsessed with antlers than we Americans are. Even now, most any pub in Germany or England will have a set of antlers on display against an impressive oak plaque; much of the time, they are just little spikes that we’d only make into knife handles.” So there we have it: to the US hunter, size matters, whereas to the average Brit, it’s just having the trophy on the wall as a physical reminder of a successful hunt that’s important.

Trophies on the gunroom wall also represent a statement of hunting prowess, and it seems that this statement can be emphasised in two ways. Either you can have big trophies, or you can have lots of trophies. The latter route is perhaps taken to its extreme in the Stag Ballroom at Mar Lodge, the walls and ceiling of which are covered with skull mounts, mostly shot on the estate between 1870 and 1910, many of them by the Royal Family. The interior of this timber building, formerly used by the estate staff for dances, really is a remarkable sight.

Today’s stalking guest in the Highlands is unlikely to have the opportunity to amass such a collection. A regular visitor, however, could quickly fill the walls of his dining-room or stairwell. In most cases, the process by which a trophy is prepared is something of which the guest is blissfully innocent. It is generally delivered to the lodge by the estate stalker on the day of a guest’s departure in exchange for the usual discreet wad of notes. It is handed over, cleaned, cut and ready for fixing to a suitable wooden shield or plaque.

SKINNED AND BOILED

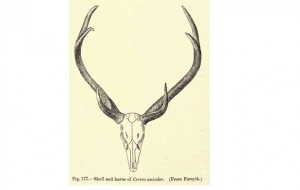

Preparing a skull mount is, however, incredibly easy, and anyone shooting a worthwhile head in circumstances where professional assistance is not available needs nothing more than a skinning knife, a saw and a large pan of boiling water. The first job is to skin the skull completely, remembering to skin right up to the tops of the pedicles. Then, using the saw, cut the skull to your preferred length so that you can fix it easily to the flat surface of a shield or plaque. Traditionally, Scottish stalkers have favoured the long nose cut, made below the eye sockets, which removes the upper teeth but leaves the oval nose bones on the trophy. Alternatively, the short or standard cut may be made from behind the back of the skull through the lower third of the eye sockets. There exist various jigs with which to hold the skull while you are cutting it, but I have never found any of these to be satisfactory and I prefer simply to place the head on a concrete floor and hold it firmly while judging the cutting angle by eye.

When the skull has been cut, place it in a pan of boiling water so that the water covers the pedicles but not the antlers. A fallow or red will require three quarters of an hour, while a muntjac will need just 20 minutes. Beware though: the smell of boiling heads may not worry the stalker, but the stalker’s wife will most probably find it highly obnoxious. I recall once making use of an enforced period of sporting downtime by boiling out a bronze-medal muntjac head on Christmas day. The rest of the family was relaxing around a log fire when the most dreadful whiff started to permeate the entire house.

I have not been allowed to forget the occasion.

WILD BOAR ON THE WALL

When the skull has boiled sufficiently that all the gristle and membrane starts to pull away from the bone, run it under cold water to cool it and then pick and scrape it clean with a short-bladed knife. Then carefully cut away the dense mass of nasal bone on the underside of the trophy, rinsing it all the time under the cold tap as you do so. I find a scouring pad very useful to finish the upper surface of the bone. Then set the skull mount aside to dry.

Deerstalking supplies firms are able to provide some very nice wooden shields on which to display your trophy, though I have to say that I prefer to make my own plaques from heavily weathered oak floorboards. I find that the deep figuring of the scrubbed oak perfectly complements the texture of bone and antler to make a natural-looking wall mount.

There is a trick, however, to fixing one to the other. You may buy a mounting bracket which is inserted into the skull and bolted directly on to the plaque, but beware, these brackets have been known to come loose in the warmth of a centrally heated house, at which point your precious trophy will crash to the floor and shatter. Much safer is to fill the back of the skull with a two-part epoxy filler and press into it a short piece of wood. When the filler is set, you may drill through from the back of the plaque and screw into the wood to fix the skull in place. This fixing is absolutely firm and quite invisible. It is quicker and cheaper to screw through the two holes in the front of the skull with brass screws, but such a fixing looks exactly that: quick and cheap.

There may come a time when you are lucky enough to fell a beast that is worthy of sending to the taxidermist in order to have it prepared as a full shoulder mount. High ceilings are essential if one is to display a collection of red deer or African game to full effect. Because they lack the headgear, however, wild boar will fit a room with a relatively low ceiling, and they make a hugely impressive shoulder mount.

The demand for trophy mounts is large and growing. “People aren’t just buying old, bleached boggle-eyed mounts from the great taxidermists like Roland Ward, Peter Spicer or Edward Gerrard; they’re increasingly interested in modern work,” says hunting trophy specialist Adam Schoon of auctioneers Tennants. “The quality of modern work is sensational, and fashion dictates that the better looking the specimen, the greater the demand will be.” Particularly active in the market is the interior decorating fraternity, who may be looking for a centrepiece for a dining-room, hall or restaurant, but there is still strong demand from trophy collectors seeking unusual species.

When the beast is lying beside you on the hill or the forest floor and you have a rush of blood to the head sufficient to make you decide that your trophy is to be sent to a taxidermist, then think carefully about how you proceed. A professional guide will know exactly what to do, but if you are on your own, then remember that many potentially wonderful specimens have been ruined by thoughtless use of the knife. “The most important thing is to make sure the skin is taken from behind the shoulder,” says taxidermist Colin Dunton. “Split the skin down the back of the neck with the larger species – a muntjac’s neck can be peeled like a sock. Then cut behind the shoulder and front legs, detach the skin up to the base of the skull and remove the skull at the atlas joint.”

BIRDS AND BEASTS

It is easy to forget these things in the heat of the moment. On one occasion in the surge of excitement at having shot a medal muntjac, I hung the beast up by its back legs to gralloch it as I usually do and had cut the neck almost down to the throat before I realised what I was doing. Fortunately the taxidermist made a good job of stitching the skin back together.

It is best to freeze your trophy prior to despatch to the taxidermist. Do not attempt to salt it. “Twenty years ago it was a complete nightmare,” says Dunton. “There was lots of stuff coming in cut short and in a terrible state, but now virtually everyone seems to know what to do, probably as a result of all the international hunting which goes on.”

Trophies do not end with large mammals. Birds are the subject of some stunning trophies, and a pheasant, partridge or grouse makes a splendid decoration in a shoot room. I have a magnificent cock pintail, struck through the neck by a single pellet from my punt gun. When I picked it from the water, it was so pristine that I simply had to take it to the taxidermist. Another trophy is my son’s first woodcock, shot when he was 12 years old in the company of my father.

But although most birds are mounted so that they appear alive, I also have a brace of stuffed pheasants dangling from orange binder twine just as though they have been lifted from the back of the gamecart. When hung in the gunroom or in the kitchen alongside a bunch of onions or garlic, they add exactly the required touch of sporting authenticity and ambience without dripping blood or becoming foul-smelling after a couple of weeks.