In August 1773, Dr Samuel Johnson and James Boswell embarked on their 83-day, 800-mile journey through the Scottish Highlands

Scotland, 1773. In the sparsely roaded northern ‘Highlands’ the countryside is wild and romantic but devoid of many of the luxuries of life. Extensive felling of the native Scots pine forests has left most of the hills covered with heather. The population is sparse. People mostly live in scattered small farms. They resent having been disarmed, and stopped by an act of an English Parliament from wearing tartan on pain of six months’ imprisonment or banishment to the colonies. The clan system has been banned but, with the rule of law far from established, clan chieftains continue to have authority. Whisky is being distilled in countless illicit secret stills. In central Scotland some 57,000 people, rich and poor, struggle to live in the tall, disease-ridden tenements, cobbled streets and stinking, narrow wynds of Edinburgh’s Old Town. Here, at its heart, lies Boyd’s Inn, terminus for stagecoaches.

It was at Boyd’s, on the evening of 14 August 1773, that two close friends met to have a meal together: the elegant 32-year-old lawyer and Scottish Laird of Auchinleck James Boswell, and the corpulent, 63-year-old, internationally renowned English lexicographer, essayist and novelist Doctor Samuel Johnson. They were unlikely friends. Apart from the disparity in their ages, Johnson had irritating mannerisms consistent with Tourette’s syndrome and was on record as having said ‘The noblest prospect which a Scotchman ever sees, is the high road that leads him to England’. Their first meeting in London 11 years previously hadn’t gone well. Johnson was pompous and abrupt, but the young lawyer had kept his temper and a week later paid a second visit to the man he greatly admired. It was the beginning of an enduring friendship.

In England fascination with all things Scottish had been influenced by a journal, published in 1771, recording the travels in Scotland of the Welsh naturalist Thomas Pennant. Johnson’s long friendship with Boswell had inspired his interest in Scotland, but after reading Pennant’s journal Johnson declared him to be ‘the best traveller I ever read’ and, according to Boswell, he was ‘propelled by a curiosity to see strange places and study modes of life unfamiliar to him’. It was this curiosity that finds him, just arrived from London by coach, with his young Scottish friend in Boyd’s Inn. The meal did little to improve Johnson’s first impression of Scotland. Tired after his eight-day coach journey from London, he asked a waiter to have his glass of lemonade made sweeter. With greasy fingers the waiter picked up a lump of sugar and dropped it into the glass. In disgust the worthy doctor threw it out of the window.

During the next three days, while staying in Boswell’s Edinburgh house, Johnson was introduced to some of his host’s distinguished friends and shown Holyrood Palace, the church of St Giles and other notable buildings – Boswell hoping that his friend wouldn’t notice the smells wafting from the wynds. Then, on Wednesday, 18 August, together with Boswell’s manservant, they left Edinburgh to spend the next 12 weeks travelling some 800 miles through the Scottish Highlands and islands.

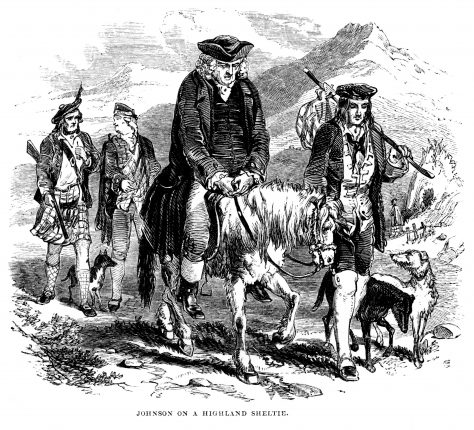

Their modes of transport depended on the roads and terrain. Where possible they hired small, horse-drawn, open or closed carriages called chaises, but west of Inverness and in the islands, where there were few roads, they hired horses or ponies and local guides who knew the countryside and the best routes to take. This must have been particularly uncomfortable and dangerous for the overweight Johnson. Where the land was boggy or they had to cross steep, heather-covered slopes they often had to dismount from their steeds and walk. Johnson bemoaned the fact that often ‘journies made in this manner are rather tedious and long. A very few miles requires several hours.’

Their chosen route, influenced by plans to avail themselves of the hospitality of Boswell’s many contacts among the Scottish landed gentry, was north along the east coast to Aberdeen, then west to Inverness and along the south side of Loch Ness to Glenelg, from where they sailed to the Isle of Skye. Where they knew no one, they stayed either in inns or private homes that traditionally offered accommodation to itinerant travellers. After spending seven weeks touring Skye and visiting the islands of Raasay, Coll and Mull (during which time they met the Jacobite heroine Flora MacDonald and Johnson spent the night in a bed that Bonnie Prince Charlie had slept in), they returned to the mainland and travelled south via Loch Lomond to Glasgow where Johnson was ‘impressed by a general appearance of wealth’. Now back in roaded country and, to their relief, able to travel by carriage again, they then journeyed south to Auchinleck in Ayrshire, where they stayed for six nights with Boswell’s father in the family home.

Despite being warned previously by Boswell not to discuss politics and religion with his father, a learned, diehard Presbyterian Scottish judge, the subjects came up and the two men had an ‘exceedingly warm and violent’ quarrel. Boswell was ‘much distressed by being present at such an altercation between two men, both of whom I reverenced’. Notwithstanding the problems, on 8 November his father ‘politely attended him to the post-chaise’ hired to take Johnson and Boswell to Edinburgh, where they arrived the next day.

Both Johnson and Boswell kept detailed journals that are rich sources of information about their travels and conditions in the Scottish Highlands in the late 18th century. They were often soaked while travelling or confined to their accommodation for days by wind and rain. Johnson lamented the fact that much of the countryside was ‘void of trees and hedges’.

Apart from recording seeing an otter in Armadale, their journals make scant reference to wildlife. The inns they stayed in varied from ‘tolerable’ and ‘indifferent’ to the inn at Glenelg where their room was ‘damp and dirty’ with ‘bare walls, bad smells [and] coarse, black, greasy tables’. Meals feature regularly in their journals. They were fascinated by the tradition of taking a dram of whisky before breakfast, had some ‘hearty dinners’ in country houses, complained about the Cheshire cheese that ‘pollutes the tea-table’ and had some good evening ‘suppers’.

My reading of his journal convinced me that the young Boswell was in awe of Johnson and revelled in the kudos he achieved by having him as a friend. The abridged version of his highly acclaimed dictionary, which was published in 1756 and sold for 10 shillings, had greatly enhanced his literary status. Boswell’s social standing must have been raised by being able to introduce Johnson to his land-owning friends and literati in the university centres of Edinburgh, St Andrews and Aberdeen. Conversation, debate and argument were social mores of the late 18th century – and Johnson revelled in them. He was neither wealthy nor particularly well-connected socially, but the research he had done during the seven years he had spent writing his 42,773-word Dictionary of the English Language, which included more than 114,000 quotations from some 500 authors, must have given him the confidence to converse on almost any subject.

During their Highland tour Johnson regaled his captive audiences with topics ranging from why trees grew upright and witchcraft to Scottish law and popery. Following a lengthy discourse by Johnson on the subject of tanning and the nature of milk, one host on the island of Skye declared him to be ‘a great orator, it is musick to hear this man speak’. But was it? In his journal Boswell records that on one occasion he was sufficiently embarrassed by his friend’s pontifications to ask him why he ‘did not practice the art of accommodation himself to different sorts of people’. But then wrote, apologetically, ‘A lofty oak will not bend like a supple willow.’

In his journal, A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland, which was published in 1775, Johnson comments on many aspects of life in the Scottish Highlands and makes particular reference to the happiness of the people. In spite of his faults, he was a truly remarkable and learned man. Unwell since birth, at an age when most men began to take things easy, he had the courage to embark upon a long, arduous tour in a little-known part of Scotland. Was he positively impressed by his experience? He wrote the following obscure lines of Latin verse during the tour:

‘I roam through clans of savage men,

Untamed by arts, untaught by pen

Or cower within some squalid den,

O’er reeking soil.’

Do they throw light on his state of mind and opinions? We will never know.