James Ward’s work, whilst reminiscent of Stubbs’s, went further, addressing the possibility that animals had feelings, says Janet Menzies

James Ward lead the way for change in his work, says Janet Menzies. While reminiscent of Stubbs, his art went further and considered the animals’ lives and their feelings, as the first major exhibition of Ward since the 1990s shows.

For more sporting artists, Andrew Kay uses the scenery that surrounds him as his canvas. And it is time for us to revaluate the work of Raoul Millais.

JAMES WARD

Viewing a James Ward oil painting of a stallion can be confusing at first. Is it a Stubbs? The composition, the subject matter, that pose with exaggeratedly arched neck and flared nostrils all seem very familiar. However, Ward (1769-1859) was working a generation later, during the Regency period. Viewed in isolation, some of Ward’s work can seem derivative but this will be contested by the new exhibition at Newmarket’s Palace House National Heritage Centre for Horseracing and Sporting Art.

Palace House curator Dr Patricia Hardy feels that seeing a Ward in isolation can give a false impression of his work as a whole. She explains: “People know about George Stubbs but we feel that Ward has been rather neglected and there hasn’t been an appreciation of the versatility and the breadth of work he produced over a very long career – he was 90 years old when he died.”

Fight Between a Lion and a Tiger, which opens the exhibition.

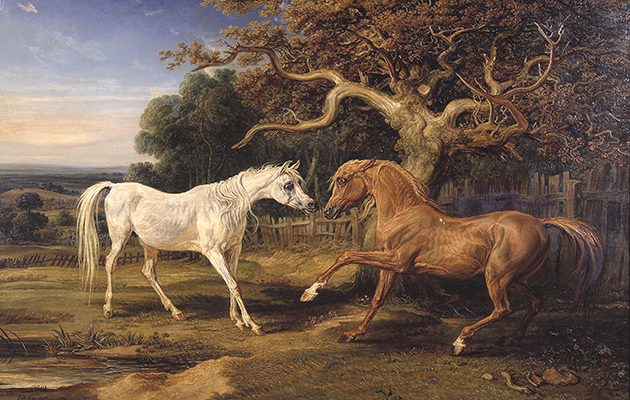

One of the most dramatic of Ward’s works, Fight between a Lion and a Tiger (1797), which opens the exhibition, seems heavily influenced by Stubbs in its subject matter and composition but another oil in the exhibition, L’Amour de Cheval, painted 30 years later in 1827, has moved a long way from that early preoccupation with menagerie animals. Dr Hardy says: “That later painting was criticised at the time because it was felt the mare was more eager than the stallion. More importantly, both animals are depicted as older and the suggestion is that their love might be emotional rather than physical. Ward was one of the first painters to address this possibility of animals’ feelings.”

Bookended between pioneering Stubbs and the great Victorian sentimentalist Landseer, it would be easy to overlook Ward’s particular contribution. Ward, however, was a contemporary of William Blake, who wrote The Tyger just three years before Ward produced his painting. Like so many artists in his circle, Ward was responding to the Romantic movement and attempting to express the sublime. Dr Hardy comments: “He was one of several artists who were depicting the arc of an animal’s life and he was trying to encourage viewers to engage with this as comparable with the growth of the human spirit. It was a change in sensibility at the time across the arts.”

A STRONG HIERARCHY

Leading the way in this change wasn’t easy for Ward. As in Stubbs’s time, there was still a strong hierarchy in what was thought a fit subject for serious art work. Allegory, history and religious topics were considered worthy of recognition, portraits and animal studies were low down the scale. Ward had been born into a poor London background, growing up among the Thames warehouses as the son of a merchant. His instinctive love of sketching and painting animals and horses was not something to be proud of. When he was made a full member of the Royal Academy in 1811, Ward told fellow artist Joseph Farington: “I don’t wish to be admitted to the Academy as a Horse-Painter.”

Acknowledging his influences, Ward made little of Stubbs, even though his early work clearly owes inspiration to his predecessor. Instead, Ward insisted on Rubens as a hero. But his own attempts at allegorical, historical and mythological subjects, including Venus Rising from her Couch, lack the vitality and credibility of his landscape and animal work. Sadly, Ward’s great venture into the world of high art, painting the recent Battle of Waterloo in his grand-scale Allegory of Waterloo, was a flop and has since been lost – possibly not a bad thing considering the reviews it received.

View in Tabley Park (1813-18).

Ward wanted prestige, including financial recognition, but his true gifts as an animal and landscape artist must have seemed to him a hindrance. Dr Hardy agrees: “While it isn’t easy to understand what Ward’s thinking must have been at the time, my intuition is that there was inner conflict in him about where he wanted his art to go.”

Luckily for us, as his career developed Ward resolved this dilemma by being to true to his love of animals. Dr Hardy says: “The great thing about an exhibition is that you have the opportunity to show the totality of the artist’s work and put it in context. By having this first major exhibition of Ward since the 1990s, we are able to show his artistic progression and especially the great love he had for working animals.

“I think Ward is one of the first to ask the viewer to think of what animals might be feeling and thinking. Later, Landseer had a more sentimental approach of imposing human emotions on the animals he depicted, whereas Ward is trying to get to grips with what the animals’ lives were actually like.”

“James Ward: Animal Painter” will be at Palace House, Newmarket, from 4 May until 28 October 2018 (tel 01638 667314; www.palacehousenewmarket.co.uk)