Roman roads pass through some of our best countryside. Do you have one near you? Then follow it and discover something new.

We follow Roman roads everyday. When we travel to a meet or set off with the dog for a shooting morning we are following in the footsteps of the Romans. Sudden stretches of arrow-straight Roman road carving through our most delightful countryside denote the remnants of the ancient road system they introduced to Britain.

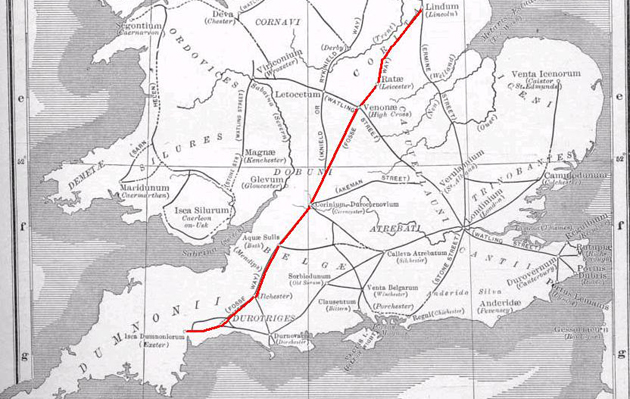

Travelling from London to Yorkshire for partridges? Then Ermine Street will guide you. Heading to Quorn country or Warwickshire for some hedge-hopping? The Fosse Way will get you there. This route is something of a hunting superhighway, ploughing as it does through some of the best hunting in the country. For 2000 years these roads have shaped our countryside and mapped our heritage. Their continued use is testament to their extraordinary utility.

A ROMAN INVASION

The Roman presence in Britain can be dated from Julius Caesar’s first abortive forays in 55BC and 54BC to the AD410 sack of Rome by the Visigoths and withdrawal of Roman government from the country. The defeat of the last Western Roman Emperor, Romulus Augustus, came in AD476. For four centuries Britannia was part of its mega-Empire.

Caesar’s first attempt to conquer the Britons led to an ignominious retreat, but the second, in 54BC, resulted in Britons paying tribute to Rome and laid the foundations for the full-scale invasion under Emperor Claudius in AD43. In a show of strength, 40,000 Imperial troops landed in Kent and made their way to Colchester. Faced with an organised, armoured, adept military force, the Britons’ resistance crumbled. When Claudius arrived, with elephants, and drove them triumphantly through Colchester, Roman victory was secured in the south-east.

But the Romans knew that an invasion without organised structure would lead swiftly to defeat. They had to subdue the population permanently, link together their Empire and brand Britannia with the Imperial seal. They did this through their roads.

Tracks and roadways were not unknown to the prehistoric Iron Age population. It is now thought that the Fosse Way had long been in use before it was Romanised. The Iron Age people in their Iron Age hillforts are believed to have been much more advanced than early archaeologists suspected, with a population perhaps as large as that recorded in the 14th century. Native Britons lived in a semi-structured society that was not wholly conquered by the Roman way of life, but was adapted and improved. Roman roads were the tool that enacted the change from Iron Age Britain to Roman Britannia.

HOW WERE ROMAN ROADS BUILT?

Vitruvius, the Roman architect, gave us the only extant record of the rules of classical architecture in his treatise De Architectura (Ten Books on Architecture). He also described how the ideal Roman road should be constructed. Built in layers up to a metre thick, the road was constructed by laying down a foundation of lime mortar or sand to form a hard, flat base (pavimentum), this was followed by large stones (statumen), a layer of smaller stones (rudus), gravel (nucleus) and finally topped with large paving stones (summum dorsum). On each side of the road a ditch was dug (fossa) and the cambered surface allowed rainwater to drain into it. The width of the road usually stood at four metres but could be as wide as nine metres depending on the importance of the route. The more important allowed two Roman chariots to pass each other.

Archaeology has proved that the Vitruvian ideal was not universally adopted. Perhaps in the centre of Rome it was a logical choice, but few roads in Britannia boasted paving stones. Most had a metalled surface of compacted gravel. This made it easier for horse-drawn chariots and unshod horses, as well as being less labour intensive. As long as the road had solid foundations, a decent surface and was well-drained it sufficed. Roman roads were often built on an embankment (agger). This allowed troops to travel along the road without fear of ambush. It also gave the structure an air of majesty. At Ackling Dyke near Blandford Forum in Dorset the remains of an agger 12 metres wide and 1.5 metres tall still exists, a definite show of Roman authority.

RECOGNISE A ROMAN ROAD

But the most recognisable feature of Roman roads is their unerring direction. They did not meander along animal tracks or watercourses, they went straight to where they intended to go. Roman surveyors used a combination of tools to achieve this. Beacons were lit along an intended route, at the start and finish and at strategic points in between. Standing at a beacon the surveyor could then sight the next beacon and maintain a straight line. To do this he used a groma, believed to be Egyptian in origin, that consisted of a horizontal, cross-shaped wooden frame on a staff with plumb-lines hanging vertically from each arm. Sighting across the plumb-lines allowed objects to be lined up accurately.

The Romans’ knowledge of geometry and the stars makes it likely they plotted the outline of the route this way and then used the groma to ensure the final result was straight. They also had a chorobates (a spirit level), a dioptre for more complex gradient measuring and a hodometer with which they could measure distance. This was particularly useful as the Romans liked to construct milestones along their main roads to let travellers and soldiers know how far they were from the next city. When large obstacles barred their way, they would divert their course by laying out another straight line. From above, a map of Britain’s Roman roads shows just how accurate and direct they were.

The Claudian invasion started at Rich-borough, where a white marble triumphal arch led on to the first Roman street. From here, a network of roads pushed into

Britannia. On their own turf, the Britons had the upper hand but by building roads the Romans turned the landscape to their advantage. They built forts and joined them with arterial highways. It helped the Empire divide the land into easily calculable areas for tax purposes and assisted the movement of soldiers. It also aided communication between Rome, Britannia and elsewhere.

The Imperial Post (cursus publicus) was a vital element of the Empire. Riders would hurry messages along the roads by relay, stopping at staging posts to hand the communication on. A distance of around 50 miles a day could be achieved by the service. The roads facilitated trade throughout the Empire, from British tin to Samian pottery. It was possible to operate a sophisticated economy as fashion and trends were dispersed and the idea of Rome prospered. More than 2,000 miles of Roman roads were constructed in Britain and in excess of 50,000 miles throughout the Empire.

THE BEST KNOWN ROMAN ROADS

In Britain, the three best known are: the Fosse Way (231 miles) from Exeter to Lincoln; Ermine Street (190 miles) from London, through Lincoln to York; and Watling Street (276 miles) from Dover to Wroxeter, largely traced by the modern A5. Akeman Street

(79 miles) joined the Fosse Way and Watling Street from St Albans to Cirencester, and

Dere Street (180 miles) went north from York through Hadrian’s Wall to the Firth of Forth. However, Wade’s Causeway, which runs from Dunsley Bay via Cawthorn to Malton in North Yorkshire, is widely regarded as the best-preserved Roman road in Britain.

The easiest way to understand the roads of Roman Britain is to view them on a map; the Ordnance Survey Map of Roman Britain is particularly good and the Tabula Peutingeriana is a medieval copy of an original Roman road map. Stretched and elongated east to west, it resembles a modern Tube map, listing stops along the roads and places to stay.

The lines of Empire still stretch through the British countryside, particularly visible to those who live and work there. Cutting between hunting countries on the perfect hunter or heading north for grouse shooting, these ancient lines remain the aqua vitae of a countryman’s travels.